The Weimar Republic

"Weimar Republic" is the name given to the German government between the end of the Imperial period (1918) and the beginning of Nazi Germany (1933). Political turmoil and violence, economic hardship, and also new social freedoms and vibrant artistic movements characterized the complex Weimar period. Many of the challenges of this era set the stage for Adolf Hitler's rise to power.

-

1

The social and economic upheaval that followed World War I powerfully destabilized the Weimar Republic, Germany's fledgling democracy, and gave rise to many radical right wing parties in Weimar Germany.

-

2

Many Germans believed that Germany had not lost the war because of military failures but had been “stabbed in the back.” The founders of the Weimar Republic, Jews, socialists, liberals, war profiteers, and others on the home front were blamed for undermining the war effort.

-

3

The Weimar Republic, Germany’s 12-year experiment with democracy, came to an end after the Nazis came to power in January 1933 and established a dictatorship.

The Weimar Republic is the name given to the German government between the end of the Imperial period (1918) and the beginning of Nazi Germany (1933).

The Weimar Republic (and period) draws its name from the town of Weimar in central Germany where the constitutional assembly met. Political turmoil and violence, economic hardship, and also new social freedoms and vibrant artistic movements characterized the complex Weimar period. Many of the challenges of this era set the stage for Hitler's rise to power, but it is only with hindsight that some say the Weimar Republic was doomed from the start.

World War I left Germany a shattered nation. Two million young men had been killed and a further 4.2 million had been wounded; in all, 19% of the male population were casualties of the war. At home, the civilian population suffered from malnutrition as a result of the Allied blockade, with starvation a serious and often fatal outcome. Workers went on strike in attempts to gain better working conditions; in 1917 alone, there were 562 separate strikes. In short, Germany was coming apart. The government, centered on an ineffective Emperor, devolved into a military dictatorship incapable of reforming the system.

Thus, in August 1918, after it became clear that Germany's last gasp military offensives had failed, Generals Hindenburg and Ludendorff passed control of the government to Chancellor Max von Baden, a moderate, and two Social Democrats to enact reforms. This transfer of power would have far-reaching effects. Those most responsible for the war itself and the accompanying human and economic disasters handed their debacle to a new civilian government which then became responsible for conducting peace negotiations.

The Weimar Republic came to bear for many the humiliation of World War I and the blame for all its accompanying hardships. In many ways, it never shook this association, particularly from the clauses of the Versailles Treaty that reduced the once proud German military to practically nothing and placed all blame for the war on Germany.

Mutiny, Unrest, and Violence

But, even before that government could come into being, the German navy chose in November to order a suicidal assault against the British navy in an attempt to salvage some honor. The sailors refused. A massive leftist mutiny began on November 3. On November 9, the Kaiser abdicated and fled the country. Unfortunately, this was too little, too late. Antiwar demonstrations and massive unrest in Bavaria followed thereafter which unseated the old regime.

In this moment of great confusion and turmoil, the army under General Wilhelm Groener offered the Social Democratic Chancellor, Friedrich Ebert, a deal. In exchange for a guarantee not to reform the officer corps or reduce the power of the armed forces, Groener promised the support of the military in maintaining order and defending the government. Faced with increasing violence from all sides, Ebert agreed in what became known as the Ebert-Groener Pact. While some historians condemn this act as a betrayal of democratic values, Ebert had few options at the time in order to maintain some semblance of law and order.

At first, however, right-wing Freikorps or volunteer paramilitary organizations were deployed against left wing agitators. The violent confrontations between left and right-wing extremists became ever bloodier. At least 1,200 Germans died in nine days of street fighting in Berlin in March 1919. Similar violence took place across Germany, most notably in Munich.

Creating a New Constitution

With the violence quelled, 25 men including the famous sociologist Max Weber, legal scholar Hugo Preuss, politician Friedrich Naumann, and historian Friedrich Meinecke worked from February to July 1919 crafting a new constitution which became law on August 11. The drafters of this new constitution faced the difficult task of creating a government acceptable to both the political left and right without being too radical. They compromised to satisfy both groups.

The basic format of the government was based around a president, a chancellor, and a parliament or Reichstag. The President was elected by a popular vote to a seven year term and held real political power, controlling the military and having the ability to call for new Reichstag elections. In a nod to conservatives afraid of too much democracy, the framers also added elements such as Article 48 which allowed the President to assume emergency powers, suspend civil rights, and operate without the consent of the Reichstag for a limited period of time.

The chancellor was responsible for appointing a cabinet and running the day-to-day operations of the government. Ideally, the chancellor was to come from the majority party in the Reichstag or if no majority existed, from a coalition. The Reichstag, in turn, was also elected by a popular vote with its seats distributed proportionally. This meant when the Social Democratic Party (SPD) won 21.7% of the popular vote in 1920, it was allocated (roughly) 21.7% of the 459 seats available (102).

This system ensured that Germans had a voice in government that they had never had before but it also allowed for a massive proliferation of parties that could make it difficult to gain a majority or form a governing coalition. For example, the Bavarian Peasants' League, a party representing purely agricultural interests in Bavaria won 0.8% of the vote and gained 4 seats. Proportional representation later allowed more extremist parties such as the Nazi Party to gain influence.

Immediate Challenges

However, the Weimar Republic faced more immediate problems in early 1920 when a group of right-wing paramilitaries seized power in what became known as the Kapp Putsch. When Ebert sought the promised help of the army in maintaining control, he was told that “the Army does not fire on other Army units.” The military, therefore, made it clear that they were happy to fight the left but would not take arms against the right-wing Freikorps. A highly effective general strike by the left saved Chancellor Ebert's government. In this strike, the national bank refused to pay out currency, civil servants refused to follow orders, and workers refused to work. Political violence peaked in 1923 with Hitler's attempted coup, the Beer Hall Putsch, which was put down by the military.

Economic Burdens

Nevertheless, the leaders of the Weimar Republic still faced daunting challenges, mainly of the economic variety, particularly the burden placed upon them by the outgoing leadership of the Kaiser and the generals. This took several forms. The first was the immense cost of the war itself and the damage it had done to Germany's civilian economy. The second was the Versailles Treaty. The Allies charged the Germans with paying staggering reparations for the cost of the war while simultaneously occupying some of the most productive regions of western Germany. For example, Germany lost 13% of its territory including areas accounting for 16% of coal and 48% of iron ore production.

The high reparations payments and costs of war had devastating consequences. The cost of living in Germany rose twelve times between 1914 and 1922 (compared to three in the United States). When the government sought to pay reparations simply by printing more money, the value of German currency rapidly declined, leading to hyper-inflation. In January 1920, the exchange rate was 64.8 Marks to one Dollar; in November 1923, it was 4,200,000,000,000 to one. This economic disaster had social consequences as well. Many Germans who considered themselves middle class found themselves destitute.

[caption=4e6611e4-63e6-449f-a269-2974f6bd0ce9] - [credit=4e6611e4-63e6-449f-a269-2974f6bd0ce9]

However, one of the overlooked successes of the Weimar government was skillfully renegotiating and restructuring its debts and bringing the economy back under control. In fact, Article 48 was used frequently by liberal chancellors to take immediate action to stabilize the economy.

Cultural Changes

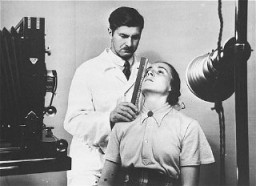

Not everything about the Weimar period was impoverishment and political turmoil. Germany experienced its own “Roaring Twenties” until they were cut short by the Great Depression. Cities burgeoned with new arrivals from the countryside in search of jobs, setting the stage for a vibrant urban life. Urban centers like Berlin became some of the most socially liberal places in Europe, much to the chagrin of conservative elites. Berlin had a thriving nightlife full of bars and cabarets. There were between 65 and 80 gay bars and 50 lesbian bars in the capital alone. Sexual liberation was a very real phenomenon, complete with a gay and lesbian rights movement led by Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld who ran an Institute for Sexual Science.

Significant increases in women's rights were another achievement of the period. The Weimar Constitution extended the right to vote to all men and women over the age of 20 in 1919 (the United States did not adopt this standard until 1920, Britain in 1928). German Jews as well experienced a period of increased social and economic freedom.

Culturally, the period produced important and lasting results. As historian Peter Gay wrote, “the republic created little; it liberated what was already there.” Weimar witnessed some of the most important developments of early film such as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919) and Nosferatu (1922). It was home to famous authors such as Franz Kafka, Vladimir Nabokov, W.H. Auden, Virginia Woolf, and Graham Greene. In the art world, Weimar featured the Expressionist works of Otto Dix and George Grosz. The plays of Bertolt Brecht appeared on German stages. The cutting edge Bauhaus movement changed the face of architecture.

Weimar also produced great thinkers like Theodor Adorno and Herbert Marcuse. German scientists won at least one Nobel Prize a year from 1918 to 1933, including a physicist named Albert Einstein.

Global Economic Crisis

However, the global economic downturn created by the Great Depression in America had devastating repercussions for the Weimar Republic. As the panic hit Wall Street, the US government pressed its former allies, Britain and France, to repay their war debts. Not having the money, Britain and France pressed Germany for more reparations payments, causing an economic depression. The German government faced the classic dilemma: cut government spending in an attempt to balance the budget or increase it in an attempt to jumpstart the economy. Heinrich Brüning, who became Chancellor in 1930, chose the deeply unpopular option of an austerity program which cut spending and those programs designed precisely to help those most in need.

Economic hardship combined with a general distrust of the Weimar system to destabilize parliamentary politics. Majorities and even coalitions in the Reichstag were difficult to form among an increasing large number of extremist parties, left and right. Elections were held more and more frequently.

Hitler's Rise to Power

A combination of political and economic dissatisfaction, some of it dating back to the founding of the Republic, helped create the conditions for Hitler's rise to power. By drawing together the fringe nationalist parties into his Nazi Party, Hitler was able to gain a sufficient number of seats in the Reichstag to make him a political player. Eventually, conservatives, hoping to control him and capitalize on his popularity brought him into the government. However, Hitler used the weaknesses written into the Weimar Constitution (like Article 48) to subvert it and assume dictatorial power.

The Weimar Republic ended with Hitler's appointment as Chancellor in 1933.

Series: The Weimar Republic

Critical Thinking Questions

- What challenges does a defeated nation face at the end of a major conflict? What responsibilities do the victors and the rest of the international community have in this situation, if any?

- What social, economic, and legal changes may have been most challenging or threatening to many Germans during the 1920s?

- How can governments and societies maintain their structure and principles in the face of dramatic social change?

- How can knowledge of the events in Germany and Europe before the Nazis came to power help citizens today respond to threats of genocide and mass atrocity in the world?