Refugees

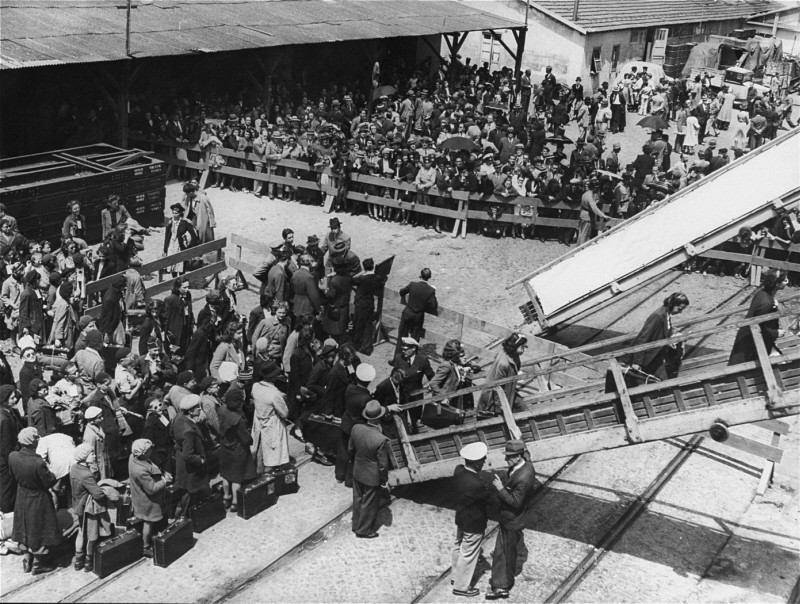

Between the Nazi rise to power in 1933 and Nazi Germany's surrender in 1945, more than 340,000 Jews emigrated from Germany and Austria. Tragically, nearly 100,000 of them found refuge in countries subsequently conquered by Germany. German authorities would deport and kill the vast majority of them. The search for refuge frames both the years before the Holocaust and its aftermath.

-

1

From 1933 to fall 1941 Nazi Germany pursued an aggressive policy of forced emigration for the Reich's Jews.

-

2

More than 340,000 Jews emigrated from Germany and Austria. Of these, about 100,000 who fled to other European countries subsequently were killed in the Holocaust.

-

3

Refugees faced enormous obstacles in finding safe havens during the Great Depression and World War II.

After Germany annexed Austria in March 1938 and particularly after the Kristallnacht pogroms of November 9–10, 1938, nations in western Europe and the Americas feared an influx of refugees. About 85,000 Jewish refugees (out of 120,000 Jewish emigrants) reached the United States between March 1938 and September 1939, but this level of immigration was far below the number seeking refuge. In late 1938, 125,000 applicants lined up outside US consulates hoping to obtain 27,000 visas under the existing immigration quota. By June 1939, the number of applicants had increased to over 300,000. Most visa applicants were unsuccessful. At the Evian Conference in July 1938, only the Dominican Republic stated that it was prepared to admit significant numbers of refugees, although Bolivia would admit around 30,000 Jewish immigrants between 1938 and 1941.

St. Louis

In a highly publicized event in May–June 1939, the United States refused to admit over 900 Jewish refugees who had sailed from Hamburg, Germany, on the St. Louis. The St. Louis appeared off the coast of Florida shortly after Cuban authorities cancelled the refugees' transit visas and denied entry to most of the passengers, who were still waiting to receive visas to enter the United States. Denied permission to land in the United States, the ship was forced to return to Europe. The governments of Great Britain, France, the Netherlands, and Belgium each agreed to accept some of the passengers as refugees. Of the 908 St. Louis passengers who returned to Europe, 254 (nearly 28 percent) are known to have died in the Holocaust. 288 passengers found refuge in Britain. Of the 620 who returned to the continent, 366 (just over 59 percent) are known to have survived the war.

Palestine

Over 60,000 German Jews immigrated to Palestine during the 1930s, most under the terms of the Haavara (Transfer) Agreement. This agreement between Germany and the Jewish authorities in Palestine facilitated Jewish emigration to Palestine. The main obstacle to emigration of Jews from Germany was German legislation banning the export of foreign currency. According to the agreement, Jewish assets in Germany would be disposed of in an orderly manner and the resulting capital transferred to Palestine through the export of German products. The British White Paper in May 1939, a policy statement approved by the British Parliament, contained measures that severely limited Jewish entry into Palestine.

Shanghai

As the number of hospitable destinations dwindled, tens of thousands of German, Austrian, and Polish Jews emigrated to Shanghai, one destination that did not require a visa. Shanghai's International Settlements quarter, effectively under Japanese control, admitted 17,000 Jews.

United States and Great Britain

During the second half of 1941, even as unconfirmed reports of the mass murder perpetrated by the Nazis filtered to the West, the US Department of State placed even stricter limits on immigration based on national security concerns. Despite British restrictions, limited numbers of Jews entered Palestine during the war through "illegal" immigration (Aliyah Bet). Great Britain itself limited its own intake of immigrants in 1938–1939, though the British government did permit the entry of some 10,000 Jewish children in a special Kindertransport (Children's Transport) program. At the Bermuda Conference in April 1943, the Allies offered no concrete proposals for rescue.

Switzerland and Spain

Switzerland took in approximately 30,000 Jews, but turned back about the same number at the border. About 100,000 Jews reached the Iberian Peninsula. Spain took in a limited number of refugees and then speedily sent them on to the Portuguese port of Lisbon. From there, thousands managed to sail to the United States in 1940–1941, although thousands more were unable to obtain US entry visas.

After World War II

After the war, hundreds of thousands of survivors found shelter as displaced persons in camps administered by the western Allies in Germany, Austria, and Italy. In the US, immigration restrictions were still in effect, although the Truman Directive of 1945, which authorized priority to be given within the quota system to displaced persons, permitted 16,000 Jewish DPs to enter the United States.

I had to wait three long years. There were quotas. There were always quotas.

—Charlene Schiff

Immigration to Palestine (Aliyah) remained severely limited until the establishment of the State of Israel in May 1948. Thousands of Jewish displaced persons sought to enter Palestine illegally: between 1945 and 1948, the British authorities interned many of these would-be immigrants to Palestine in detention camps on Cyprus.

With the establishment of Israel in May 1948, Jewish refugees began streaming into that new sovereign state. Some 140,000 Holocaust survivors entered Israel during the next few years. The United States admitted 400,000 displaced persons between 1945 and 1952. Approximately 96,000 (roughly 24 percent) of them were Jews who had survived the Holocaust.

The search for refuge frames both the years before the Holocaust and its aftermath.

Series: Rescue and Resistance during the Holocaust

Further Reading

Baumel, Judith Tydor. Unfulfilled Promise: Rescue and Resettlement of Jewish Refugee Children in the United States, 1934–1945. Juneau, AK: Denali Press, 1990.

Breitman, Richard, and Alan M. Kraut. American Refugee Policy and European Jewry, 1933–1945. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987.

Fox, Anne L., and Eva Abraham-Podietz. Ten Thousand Children: True Stories Told by Children Who Escaped the Holocaust on the Kindertransport. West Orange, NJ: Behrman House, 1999.

Genizi, Haim. America's Fair Share: The Admission and Resettlement of Displaced Persons, 1945–1952. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1993.

Laqueur, Walter. Generation Exodus: The Fate of Young Jewish Refugees from Nazi Germany. Hanover, NH: Brandeis University Press, 2001.

Zucker, Bat-Ami. In Search of Refuge: Jews and US Consuls in Nazi Germany, 1933–1941. London: Vallentine Mitchell, 2001.