Liberation of Nazi Camps

As Allied troops moved across Europe against Nazi Germany in 1944 and 1945, they encountered concentration camps, mass graves, and other sites of Nazi crimes. The unspeakable conditions the liberators confronted shed light on the full scope of Nazi horrors. 2020 marked the 75th anniversary of the liberation of prisoners from Nazi concentration camps and the end of Nazi tyranny in Europe.

-

1

Soviet forces liberated Auschwitz—the largest killing center and concentration camp complex—in January 1945.

-

2

American forces liberated concentration camps including Buchenwald, Dora-Mittelbau, Flossenbürg, Dachau, and Mauthausen.

-

3

British forces liberated concentration camps in northern Germany, including Neuengamme and Bergen-Belsen.

Majdanek and Auschwitz

The first major Nazi camp to be liberated was Majdanek, located in Lublin, Poland. It was liberated in the summer of 1944 as Soviet forces advanced westward. The previous spring, the SS had evacuated most of the Majdanek prisoners and camp personnel. The evacuated prisoners were sent to concentration camps further west, such as Gross-Rosen, Auschwitz, and Mauthausen. As the Soviet troops approached Majdanek at the end of July, the remaining camp personnel hastily abandoned the Majdanek concentration camp without fully dismantling it.

Soviet troops first arrived at Majdanek during the night of July 22–23 and captured Lublin on July 24. Majdanek was captured virtually intact. At Majdanek, the Soviet troops encountered a number of prisoners who had not been evacuated in the spring, mostly Soviet prisoners of war. They also encountered substantial evidence of the mass murder committed at Majdanek by Nazi Germans. Soviet officials invited journalists to inspect the camp and evidence of the horrors that had occurred there.

Six months later, on January 27, 1945, Soviet troops liberated Auschwitz. Auschwitz was the largest Nazi killing center and concentration camp complex. In the weeks preceding the arrival of Soviet units, Auschwitz camp personnel had forced the majority of Auschwitz prisoners to march westward in what would become known as "death marches." When they entered the camp, Soviet soldiers found over six thousand emaciated prisoners alive. These prisoners greeted the soldiers as their liberators.

As at Majdanek, there was abundant evidence of mass murder in Auschwitz. The retreating Germans had destroyed most of the warehouses in the camp. But in those warehouses that remained, Soviet soldiers found personal belongings of the victims. Among these personal items were hundreds of thousands of men's suits, more than 800,000 women’s garments, and more than 14,000 pounds of human hair.

In the following months, Soviet units liberated additional camps in the Baltic states and Poland. Shortly before Germany's surrender in May 1945, Soviet forces liberated the Stutthof, Sachsenhausen, and Ravensbrück concentration camps.

Other Camps

Shortly after the Soviet capture of Majdanek in July 1944, Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler ordered that prisoners in all concentration camps and subcamps in the German-occupied east be forcibly evacuated into the interior of the Reich. Thus, as Allied troops launched offensives within Germany, they encountered tens of thousands of concentration camp prisoners. Most of these prisoners were suffering from starvation and disease.

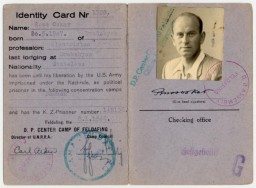

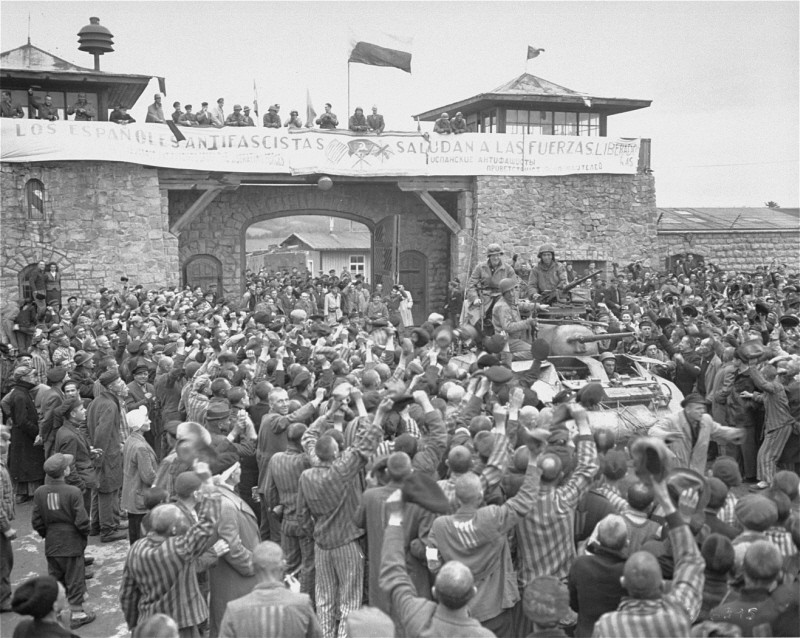

US forces liberated the Buchenwald concentration camp near Weimar, Germany, on April 11, 1945. Earlier that day before the arrival of US troops, an underground prisoner resistance organization seized control of Buchenwald to prevent atrocities by the retreating camp guards. When American forces arrived, they encountered more than 20,000 prisoners at Buchenwald. That April, US troops also liberated Dachau, Dora-Mittelbau, and Flossenbürg. They liberated Mauthausen in early May.

British forces liberated concentration camps in northern Germany, including Neuengamme and Bergen-Belsen. They entered the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, near Celle, in mid-April 1945. Some 60,000 prisoners, most in critical condition because of a typhus epidemic, were found alive. More than 13,000 of them died from the effects of malnutrition or disease within a few weeks of liberation.

Impact of Liberation

Liberators confronted unspeakable conditions in the Nazi camps, where piles of corpses lay unburied. Only after the liberation of these camps was the full scope of Nazi horrors exposed to the world. The small percentage of inmates who survived resembled skeletons because of the demands of forced labor and the lack of food, compounded by months and years of maltreatment. Many were so weak that they could hardly move. Disease remained an ever-present danger, and many of the camps had to be burned down to prevent the spread of epidemics. Survivors of the camps faced a long and difficult road to recovery.

Series: Liberation of Nazi Camps: Encountering and Documenting Atrocities

Series: After the Holocaust

Switch Series

Critical Thinking Questions

- What challenges did the Allied forces face when they encountered the camps?

- What challenges immediately faced survivors of the Holocaust?

Further Reading

Abzug, Robert H. GIs Remember: Liberating the Concentration Camps. Washington, DC: National Museum of American Jewish History, 1994.

Abzug, Robert H. Inside the Vicious Heart: Americans and the Liberation of Nazi Concentration Camps. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Bridgman, Jon. End of the Holocaust: The Liberation of the Camps. Portland, OR: Areopagitica Press, 1990.

Chamberlin, Brewster S., and Marcia Feldman, editors. The Liberation of the Nazi Concentration Camps 1945: Eyewitness Accounts of the Liberators. Washington, DC: United States Holocaust Memorial Council, 1987.

Goodell, Stephen, and Kevin Mahoney. 1945: The Year of Liberation. Washington, DC: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 1995.

Goodell, Stephen, and Susan D. Bachrach. Liberation 1945. Washington, DC: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 1995.