Defining the Enemy

A key part of Nazi ideology was to define the enemy and those who posed a threat to the so-called “Aryan” race. Nazi propaganda was essential in promoting the myth of the “national community” and identifying who should be excluded. Jews were considered the main enemy.

-

1

A number of groups were targeted as enemies or outsiders. They included Jews, Roma (Gypsies), homosexuals, and political dissidents. Also targeted were Germans viewed as genetically inferior and harmful to “national health,” such as people with mental illness and intellectual or physical disabilities.

-

2

The use of propaganda and laws to define the enemy as a cohesive group was a key factor in achieving the goals of the Nazi regime.

-

3

These campaigns incited hatred or cultivated indifference to it. They were particularly effective in creating an atmosphere tolerant of violence against Jews.

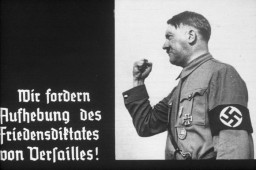

The Nazi Party Program

In February 1920, Hitler presented a 25-point Program (the Nazi Party Platform) to a Nazi Party meeting.

In the 25-point program, Nazi Party members publicly declared their intention to segregate Jews from "Aryan" society and to revoke Jews' political, legal, and civil rights. Point 4 of the program, for example, stated that

"Only a national comrade can be a citizen. Only someone of German blood, regardless of faith, can be a citizen. Therefore, no Jew can be a citizen."

The 25 points remained the party's official statement of goals, though in later years many points were ignored.

Anti-Jewish Propaganda

While there were other antisemitic political parties, only the Nazi Party succeeded in gaining a mass following. Nazi propagandists exploited pre-existing images and stereotypes to give a false portrayal of Jews. In this false view, Jews were an “alien race” that fed off the host nation, poisoned its culture, seized its economy, and enslaved its workers and farmers. The Nazis claimed that “race mixing” through marriage weakened Germany.

This hateful depiction, although neither new nor unique to the Nazi Party, became a state-supported image. As the Nazi regime tightened control over the press and publishing after 1933, propagandists tailored messages to diverse audiences. These audiences included the many Germans who were not Nazis and who did not read the party papers.

Public displays of antisemitism in Nazi Germany took a variety of forms, from posters and newspapers to films and radio addresses. Propagandists offered more subtle antisemitic language and viewpoints for educated, middle-class Germans offended by crude caricatures. University professors and religious leaders gave antisemitic themes respectability by incorporating them into their lectures and church sermons.

Additional Outsiders

Jews were not the only group excluded from the vision of the "national community." Propaganda helped to define who would be excluded from the new society and justified measures against the "outsiders." These so-called outsiders included Jews, Roma (Gypsies), homosexuals, Jehovah's Witnesses, and Germans viewed as genetically inferior and harmful to "national health" (people with mental illness and intellectual or physical disabilities, epileptics, congenitally deaf and blind persons, chronic alcoholics, drug users, and others).

As a German woman active in Nazi youth programs wrote in her postwar memoirs

“I became a National Socialist because the idea of the National Community inspired me... What I had never realized was the number of Germans who were not considered worthy to belong to this community.”

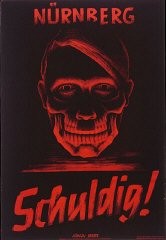

Identification, Isolation, and Exclusion

Propaganda also helped lay the groundwork for the announcement of major anti-Jewish statutes at Nuremberg on September 15, 1935—the Nuremberg Race Laws. The decrees followed a wave of anti-Jewish violence perpetrated by impatient Nazi Party radicals. Two distinct laws made up the Nuremberg Laws. The Law for the Protection of German Blood and Honor prohibited marriage and extramarital sexual relations between Jews and persons of “German” or “related blood.” The Reich Citizenship Law defined Jews as “subjects” of the state, a second-class status.

The laws affected some 450,000 “full Jews” (defined as those with three or four Jewish grandparents and belonging to the Jewish religion), and 250,000 others (including converted Jews and Mischlinge, those with some Jewish parentage). Together they accounted for less than than one percent of the German population. For months before the announcement of the Nuremberg Laws, the Nazi Party press aggressively incited Germans against racial pollution, with the presence of Jews in public swimming pools becoming a major theme.

Control of Cultural Institutions

Through their control of cultural institutions, such as museums, under the Reich Chamber of Culture, the Nazis created new opportunities to disseminate anti-Jewish propaganda. Most notably, an exhibition entitled Der Ewige Jude (The Eternal Jew) attracted 412,300 visitors, more than 5,000 per day, during its run at the Deutsches Museum in Munich from November 1937 to January 1938. Special performances by the Bavarian State Theater, reiterating the exhibition's antisemitic themes, accompanied the exhibition. The Nazis also associated Jews with “degenerate art,” the subject of a companion exhibition in Munich seen by two million people.

A later film of the same name contained notorious antisemitic sequences. These scenes compared Jews to rats that carry contagion, flood the continent, and devour precious resources. Der ewige Jude is distinctive for many reasons. It contained crude, vile characterizations made worse with its gruesome footage of a Jewish ritual butcher at work slaughtering cattle. It also included a heavy emphasis on the allegedly alien nature of the east European Jew. In one of the film's sequences, “stereotypical” Polish Jews with beards are depicted as shaven clean and transformed into “western-looking” Jews. Such “unmasking” scenes aimed to show German audiences that there was no difference between Jews living in east European ghettos and those inhabiting German neighborhoods.

Der ewige Jude ends with Hitler's infamous speech to the Reichstag on January 30, 1939: “If international Jewish financiers inside and outside Europe should succeed in plunging the nations once more into a world war, then the result will not be the…victory of Jewry but the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe.” The speech appeared to be a sign of radicalization of the solution to the “Jewish Question” in the coming “Final Solution,” and provided a foreshadowing of mass murder.

Inciting Hate and Popularizing Indifference

While most Germans disapproved of anti-Jewish violence, dislike of Jews, easily stirred up in hard times, extended far beyond the Nazi Party faithful. The majority of Germans at least passively accepted discrimination against Jews. An underground report prepared in January 1936 by an observer for German Social Democratic Party leaders in exile noted: “The feeling that the Jews are another race is today a general one.”

During periods preceding new measures against Jews, propaganda campaigns created an atmosphere tolerant of violence against Jews. In some cases the campaigns exploited the violence—both calculated and spontaneous—that ensued. The goal was to encourage passivity and acceptance of anti-Jewish laws and decrees as a vehicle to restore public order. Propaganda that demonized Jews also served to prepare the German population, in the context of national emergency, for harsher measures, such as mass deportations and, eventually, genocide.

Critical Thinking Questions

- How can propaganda and the spread of harmful misinformation about a particular group be identified and countered?

- What options are available when a nation legally defines a minority as second-class or subhuman? Can or should other nations be involved?

- How can knowledge of the events in Germany and Europe before the Nazis came to power help citizens today respond to threats of genocide and mass atrocity in the world?