“Give Me Your Children”: Voices from the Lodz Ghetto

Lodz

The German invasion and conquest of half of Poland in September 1939 put nearly 2 million Jews under Germany’s jurisdiction. Among them were the more than 233,000 Jews of Lodz, Poland’s second largest city after Warsaw. Throughout occupied Poland, the Germans quickly imposed anti-Jewish policies.

The Jewish children of Lodz suffered unfolding harsh realities after the German invasion of Poland. Some of the children recorded their experiences in diaries. Their voices offer a view into the struggle of a community and its young to live in spite of the most difficult circumstances.

Why Do They Separate Us?

“One day, little Rysia asked if Jews looked different before the war from the way they looked now and if they ever looked like non Jewish people. After hearing that there is no real difference between non-Jews and Jews, she contemplated this for a moment and finally asked: ‘So why do they separate us from them?’”

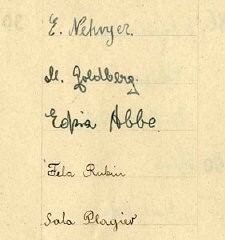

—Sara Plagier, age 15“The yellow badge was a kind of stamp. A stamp that distinguished me from the rest of the population. Anyone could approach me, tell me, do to me whatever they wanted.”

—Jutta Szmirgeld, age 12

The order to wear yellow Stars of David made Polish Jews of all ages targets for humiliation and violence. German-established ghettos segregated and subjugated Jews to stringent control. On May 1, 1940, the Lodz ghetto was sealed, enclosing some 164,000 Jews who had not fled or been deported to await an unknown fate under their German rulers.

“The Ghetto is Only a Transitional Measure”

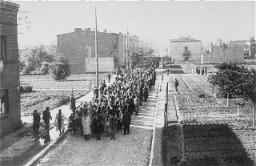

From early February to late April 1940, the Germans herded some 100,000 Jews into three impoverished neighborhoods of Lodz. More than 700 people were murdered during the upheaval. The ghetto, encircled in barbed wire and guarded by armed German police, was put under the supervision of Hans Biebow, a 38-year-old German businessman. A complex German bureaucracy organized the systematic confiscation of the Jews’ valuables and the exploitation of their labor.

“The establishment of the ghetto is only a transitional measure. I reserve for myself the decision as to when and how the city of Lodz will be cleansed of Jews. The final aim must be to burn out entirely this pestilential boil.”

—Friedrich Übelhör, German governor of the Kalisz-Lodz district, December 10, 1939

“A Small-Scale City”

The full burden of the ghetto’s daily life fell to one Jew—Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski. Caught between his accountability to the Germans and responsibility for the Jews, Rumkowski was forced to comply with non-negotiable German demands while he struggled to provide for the ghetto’s needs. He directed a Jewish administrative bureaucracy that allocated shelter, rationed food and fuel, and maintained order. Separate departments regulated ghetto industries, schools, health institutions, and social welfare for orphans and the elderly.

Six weeks have elapsed since the ghetto was completely closed off. I have had to start building from the ground up an administrative apparatus that the ghetto—a small-scale city—requires.”

—Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski, June 12, 1940

“Does this Deserve To Be Called Life?”

When the ghetto was closed, more than 160,000 people were jammed into 1-1/2 square-miles of old wooden buildings, as many as 8 to 10 per room. Most of the houses lacked basic plumbing. Chronic shortages of food, inadequate clean water, scarce fuel, and primitive sanitation caused thousands to die from starvation, malnutrition, and disease.

“When it’s so cold, even my heart is heavy. There is nothing to cook today; we should be receiving three loaves of bread but we will be getting only one bread today. I don’t know what to do. I bought rotten and stinking beets from a woman, for 10 marks. We will cook half today and half tomorrow. Does this deserve to be called life?”

—Anonymous girl diarist, March 6, 1942“In the ghetto we had no need for a calendar. Our lives were divided into periods based on the distribution of food: bread every eighth day, the ration once a month Each day fell into two parts: before and after we received our soup. In this way the time passed.”

—Sara Plagier, age 14

“Will I Ever Live in Better Times?”

“Beautiful, sunny day today. When the sun shines, my mood is lighter. How sad life is. When we look at the fence separating us from the rest of the world, our souls, like birds in a cage, yearn to be free. ... Will I ever live in better times?”

—Anonymous girl diarist, March 7, 1942Good Mr. Chairman,

My name is Sarenka Lewi. I am 9 years old. My daddy works very hard, but he cannot feed our family. Aside from dried bread and soup from the soup kitchen, we do not have anything else. Dear Mr. Chairman, please put in a good word at the hat-making workshop to give my Mommy a job. Good Grandpa, have mercy on hungry Sarenka and write such a letter. I am very tired now. ... I would like so much to survive the war.

—Sarenka Lewi

8 June 1941

“I Never Had Such Marvelous Hours”

Despite the pervasive miseries of hardships and hunger, young people in the ghetto still found happiness and hope. Many young Jews continued to observe the rituals and practices of their religion. Others helped establish political youth groups for cultural, social, and intellectual pursuits. Public lectures, poetry readings, and musical performances, including performances by and for children, also provided relief from the daily gloom. Just the companionship and joy of friendships helped to offset the personal anguish of ghetto life.

“It was forbidden to gather more than three or five people. It was punishable by death, but we were sometimes even fifteen teenagers, and we were then in Palestine for this hour with the organization. This was the land of Israel; we were not in the ghetto. I never had such marvelous hours. I ran to my organization and there I forgot. I forgot my mother. I forgot my brother. It’s not nice, but I really forgot. The life was different there. There, I saw the blue sky with stars. The sky of the land of Israel.”

—Jutta Szmirgeld, age 14“The day of my Bar Mitzvah arrived. I put on the tefillin and I said the blessings. As a gift from my family I received half a loaf of bread. They wanted me to eat it right there and then, in their presence. I refused. I couldn’t even imagine for how long they saved it from themselves in order to give it to me. They decided that I had to eat it, and I ate it. I couldn’t look them in the eye because I ate their bread.”

—Chaim Kozienicki, age 13

“So I'll Go To School Again”

Jewish communities have traditionally held education in the highest regard. While in many ghettos established by Nazi officials, such as the Warsaw ghetto, schools for Jewish pupils and students were banned, the Lodz ghetto was initially an exception. Of the 60 Jewish elementary, secondary, and religious schools active in Lodz when the Germans invaded, more than 40 continued to function after the ghetto was closed. The classrooms were overcrowded and ill equipped, but the routines and camaraderie of study offered almost 15,000 students an environment of normalcy and relief from the ghetto’s oppressive misery. At school, the children also received one meal a day, which often meant the difference between life and death.

“I have registered at the school secretariat at Dworska Street. There will be additional nutrition in school, but details won’t be known until Friday. So I’ll go to school again. There will finally be an end to the anarchy in my daily activities and, I hope, an end to too much philosophizing and depression.”

—David Sierakowiak, age 16, April 22, 1941“I wanted to go to school not so much to learn, but to eat the soup and not be frozen.”

—Chaim Cale, age 13

“For The School And The Meals—Our Heartfelt Thanks”

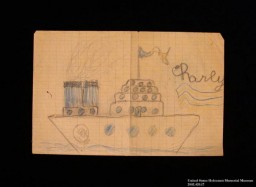

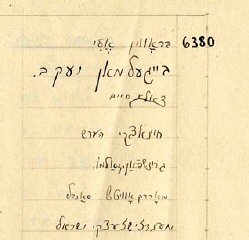

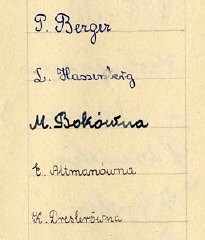

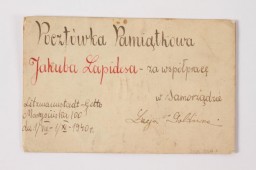

On September 23, 1941, on the occasion of the Jewish New Year (Rosh Hashanah), the Lodz ghetto schoolchildren presented Rumkowski with an elaborate album of hand-drawn New Year’s greetings from 43 of the ghetto’s schools. Included, too, were signatures representing some 14,000 of the students. The greetings combine traditional holiday wishes with thanks for the schools and for the daily meals.

“The apartment swarmed with children who had been sent as delegates from the elementary schools, middle schools, orphanages, summer camps, etc. The schoolchildren presented the chairman with a beautifully made album containing more than 14,000 signatures. Each school had included a decorated card with the name of the school in the album. The Chairman made a short speech to the children thanking them for coming and wishing them a Happy New Year.”

—Chronicle of the Lodz Ghetto, September 1941"For your tireless efforts for us children,

for the school and the meals—

our heartfelt thanks

Happy New Year. May you be inscribed in the Book of Life"

School No. 20a

“The Schools Will Close”

The very afternoon that the school album was being presented, Rumkowski was summoned to meet German ghetto chief Hans Biebow. German authorities, Rumkowski learned, were deporting to Lodz 20,000 central European and Polish Jews and 5,000 Roma (“Gypsies”). Housing had to be found in an already overcrowded ghetto. The only option was to close the schools.

“Nicely dressed people arrived. They spoke German. One asked, “Where can I buy cheese?” They suffered more than we did because we were already used to it.”

—Chaim Kozienicki, age 13“I’ll start my work in the saddlery workshop tomorrow. My student career has been suspended, at least for a while. The main thing now is to make an income and survive poverty.”

—Dawid Sierakowiak, age 17, October 23, 1941

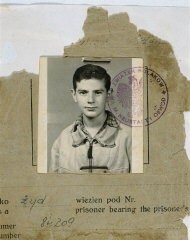

“Work Protects Us From Annihilation”

Rumkowski believed that making the Jewish ghetto useful to its German masters was the community’s path to survival. All those able to work joined 12- to 14-hour shifts in grim conditions for a little pay in ghetto currency and a ration of bread and thin soup that barely relieved their hunger. Boys and girls aged 14 and older began entering the labor force in spring 1941. When the schools closed that autumn, children as young as 10 took places at the workbenches. The workshops became the new schools, for vocational training, Yiddish, arithmetic, and a little general education. By the summer of 1942, nearly 20 percent of the workshop laborers were children and adolescents.

“My long-standing slogan, ‘Work,’ has proved itself from the start. We have seen many times over that only work brings calm. Experience has made it clear that, in our times, the basic law is that work protects us from annihilation.”

—Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski, March 2, 1942“We sewed small dresses, houndstooth pattern. For two years same cut, same dress. I sewed sleeves, small sleeves with a cuff.”

—Rut Berlinska, age 13

“Like a Stone in Water They Disappeared”

In mid-December 1941, German authorities ordered the first large-scale evacuation from the ghetto. The ghetto’s Resettlement Commission, in consultation with Rumkowski, drew up deportation lists that included unproductive ghetto residents, thousands of the recently arrived central European and Polish Jewish families, and all the Roma in habitants. Between January and May 1942, German authorities forcibly removed some 55,000 Jews, including nearly 15,000 children under age 14.

“Like a Stone in Water They Disappeared”

—Arie Princ“We are not considered humans at all; just cattle for work or slaughter. No one knows what happened to the Jews deported from Lodz. No one can be certain of anything now. They are after Jews all over the Reich.”

—Dawid Sierakowiak, age 17, May 20, 1942

“Give Me Your Children”

On September 1, 1942, German military trucks pulled up to the ghetto’s hospitals, and SS troops emerged to seize the patients. Panic swept the ghetto. On September 2, the Germans ordered the Jewish ghetto authorities to prepare 20,000 people for deportation: the sick, the elderly, and the children.

On September 4, at 4:00 p.m., Rumkowski stood before the Jews of the ghetto to announce the horrendous news, aware that his refusal to meet the Germans’ demands could lead to unimaginable consequences for everyone.

“A grievous blow has struck the ghetto. They are asking us to give up the best we possess—the children and the elderly. I never imagined I would be forced to deliver this sacrifice to the altar with my own hands. In my old age, I must stretch out my hands and beg. Brothers and sisters: Hand them over to me! Fathers and mothers: Give me your children! . . .

—Chaim Rumkowski, September 4, 1942

“From House to House”

Beginning the day after Rumkowski’s address, a general curfew—allgemeine Gehsperre—kept the Jews in their homes for eight days. Building by building, the German SS and police authorities, assisted by the Jewish ghetto police and firemen, assembled, inspected, and selected the elderly, the ill, and children under age 10 for deportation. Apartments were searched for people attempting to hide. Those who tried to flee were shot. More than 500 Jews were murdered during the round-up. Accompanied by the shrieks and wails of the victims and the spared alike, the methodical search of the ghetto tore 15,000 victims—including 6,000 children—from their families. All were sent to certain death.

“I went home. I got closer and then I saw my brother in front of the house. I approached my brother and he said, ‘Jutta, they took Grandma, they took Mom, but Mother said that you should not cry, that she will return.’ I am nothing without my mother. What could I do to save my mother?”

—Jutta Szmirgeld, age 15“I saw two wagons full of little children drive past the open gate. Many of the children were dressed in their holiday best, the little girls with colored ribbons in their hair. In spite of the soldiers in their midst, the children were shrieking at the top of their lungs. They were calling out for their mothers.”

—Sara Plagier, age 16

Chelmno

The deportation trains traveled 37 miles northwest to the Chelmno killing center. Arriving Jews were greeted by the camp’s German staff, who spoke of work, better food, and a shower. After leaving their clothes behind for disinfection, the Jews crowded into vans to ride to the baths. These vehicles at Chelmno were not ordinary trucks, but gas vans, engineered to divert deadly carbon monoxide gas from the engine exhaust into the cargo compartments. German guards sealed the airtight doors, and the driver started the engine. After 5 to 10 minutes, the screams from the suffocating prisoners stopped. The bodies were buried in mass graves.

Beginning in spring 1942, the gassed victims’ bodies were destroyed in one of two crematoria built two miles from the camp’s headquarters. The ashes of Chelmno’s dead, including the Lodz ghetto children, were buried in the nearby fields.

Epilogue

More than 200,000 Jews passed through the ghetto during its 4-year existence:

43,500 died, most of starvation and disease

11,000 were sent to other labor camps

Approximately 77,000 Jews and about 4,300 Roma ("Gypsies") from the Lodz ghetto were taken to the Chelmno killing center between December 1941 and July 1944.

As part of the final liquidation of the ghetto, beginning on August 2, 1944, more than 72,000 people—including ghetto leader Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski—were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Most, including Rumkowski, were immediately murdered.

An estimated 5,000-7,000 Lodz Jews survived to the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau (January 27, 1945) or in labor camps. Soviet forces found 870 Jews still in Lodz when they liberated the city on January 19, 1945.

Hans Biebow, the chief of the German ghetto administration, was put on trial in a postwar Polish court and was executed in June 1947.

Series: Diaries

Series: Young Diarists from the Lodz Ghetto

Switch Series

Critical Thinking Questions

- Why did the Nazis resort to a system of ghettos?

- Besides armed resistance, in what other ways did the Jews resist the Nazis while forced to live in the ghettos?

- How does the history of the Lodz ghetto and its inhabitants illustrate the systematic nature of the “Final Solution?”

- Investigate the differing views of Rumkowski’s rule and choices.

- Learn about the life and death of children in other ghettos.

Further Reading

The Chronicle of the Lodz Ghetto 1941-1944, edited by Lucjan Dobroszycki (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1984).

The Diary of Dawid Sierakowiak, edited by Alan Adelson, translated by Kamil Turowski (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996).

Lodz Ghetto: Inside a Community under Siege, compiled and edited by Alan Adelson and Robert Lapides (New York: Viking, 1989).

Isaiah Trunk, Lodz Ghetto: A History, translated and edited by Robert Moses Shapiro, introduction by Israel Gutman (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, published in association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2006).

Josef Zelkowicz, In Those Terrible Days: Notes from the Lodz Ghetto, edited by Michal Unger, translated by Naftali Greenwood (Jerusalem, Yad Vashem, 2002).

Sara Plagier Zyskind, Stolen Years (Minneapolis: Lerner Publishing Group, 1981).