Antisemitism in History: The Era of Nationalism, 1800–1918

Beginning in the nineteenth century with Great Britain and ending with the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans, the European nations established in constitutions the principle of equality under the law. They dropped all restrictions on residence or occupational activities for Jews and other national and religious minorities.

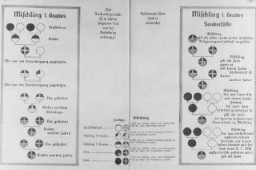

At the same time, the societies of Europe underwent rapid economic change and social dislocation. The emancipation of the Jews allowed them to live and work among non-Jews, but exposed them to a new form of political antisemitism. It was secular, social, and influenced by economic considerations, though it often reinforced and was reinforced by traditional religious stereotypes.

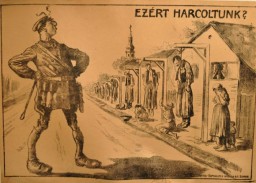

The emancipation of the Jews enabled them to own land, enter the civil service, and serve as officers in the national armed forces. It created the impression for some others—particularly those who felt left behind, traumatized by change, or unable to achieve occupational satisfaction and economic security in accordance with their expectations—that Jews were displacing non-Jews in professions traditionally reserved for Christians. It also created for some the impression that at the same time, Jews were being overrepresented in future-oriented professions of the late nineteenth century: finance, banking, trade, industry, medicine, law, journalism, art, music, literature, and theater.

The collapse of restraints on political activism and the broadening of the electoral franchise on the basis of citizenship, not religion, encouraged Jews to be more politically engaged. Though active all along the political spectrum, Jews were most visible—due to increased opportunities—among liberal, radical, and Marxist (Social Democratic) political parties.

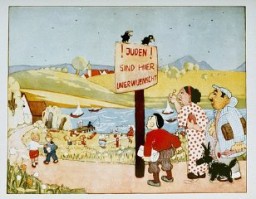

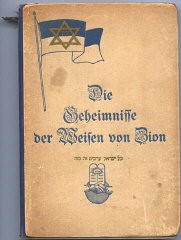

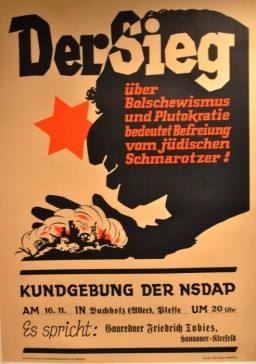

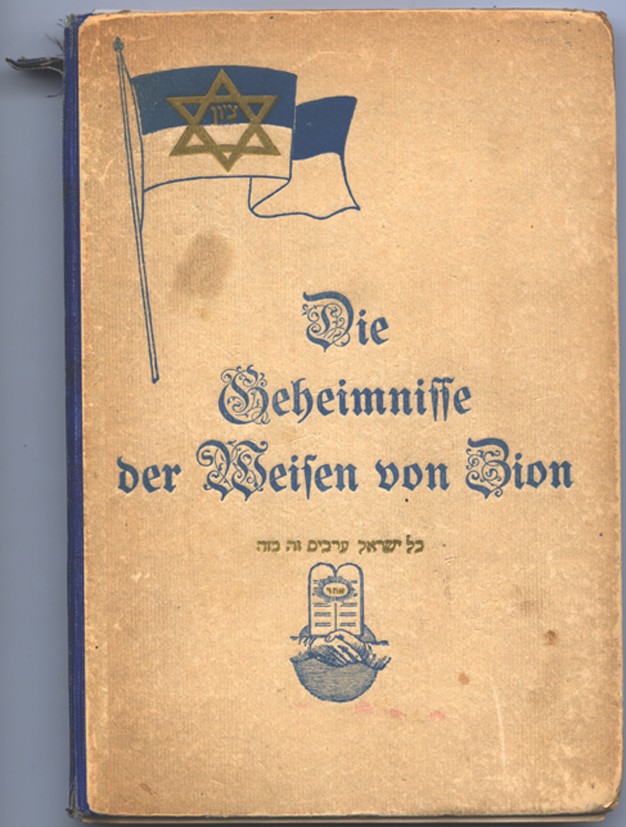

The introduction of compulsory education and the broadening of the franchise toward universal suffrage spawned the development of antisemitic political parties and permitted existing parties to use antisemitic rhetoric to obtain votes. Publications such as the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which first appeared in 1905 in Russia, generated or provided support for theories of an international Jewish conspiracy.

As religious confession became subsumed in European political culture by national identity and nationalist sentiment, a new series of stereotypes that reinforced and was reinforced by older prejudices fueled antisemitic politics:

- Enjoying the benefits of citizenship, Jews were nevertheless secretly disloyal—their "conversion" was only for material gain

- Jews displaced non-Jews in traditionally "noble" professions and activities (land ownership, the officer corps, the civil service, the teaching profession, the universities), while they "clannishly" blocked the entry of non-Jews into professions that they controlled and that represented the future prosperity of the nation (for example, industry, trade, finance, and the entertainment industry)

- Jews used their disproportionate control of the media to mislead the "nation" about its true interests and welfare

- Jews had assumed the leadership of the Social Democratic, and later, Communist movements in order to destroy middle class values of nation, religion and private property.

These prejudices bore little relationship to political, social, and economic realities in any European country. This fact did not, however, matter to those who became attracted to the political expression of these prejudices.

Series: Antisemitism

Critical Thinking Questions

- How did Nazi antisemitism build on previous beliefs and attitudes?

- How was Nazi antisemitism different than previous hatreds of Jews?

- Why do people generalize characteristics for an entire group? How can this be dangerous?

- How can deep-seated hatreds be countered?

- How can knowledge of the events in Germany and Europe before the Nazis came to power help citizens today respond to threats of genocide and mass atrocity in the world?