Auschwitz Through the Lens of the SS: A Tale of Two Albums

Shortly after World War II, an American intelligence officer living in Germany uncovered a personal album of photographs chronicling SS officers’ activities at Auschwitz-Birkenau. The Museum received this photograph album in 2007. The rare images show Nazis singing, hunting, and even trimming a Christmas tree. They provide a chilling contrast to the photographs of thousands of Hungarian Jews deported to Auschwitz at the same time.

The only other known album of photographs taken at Auschwitz, published as the "Auschwitz Album" (first published in 1980), specifically depicts the arrival of the Hungarian Jews and the selection process that the SS imposed upon them.

Auschwitz Through the Lens of the SS: A Tale of Two Albums

A comparison of Höcker's album to "Auschwitz album" is both fitting and necessary. The original owner of that album, Lili Jacob (later Zelmanovic Meier), was deported with her family to Auschwitz in late May 1944 from Bilke (today: Bil'ki, Ukraine), a small town near Berehovo in Transcarpathian Rus which was then part of Hungary. They arrived on May 26, 1944, the same day that professional SS photographers photographed the arrival of the train and the selection process. Richard Baer and Karl Höcker arrived at Auschwitz mere days before the arrival of this transport. After surviving Auschwitz, forced labor in Morchenstern, a Gross-Rosen subcamp, and transfer to Dora-Mittelbau where she was liberated, Lili Jacob discovered an album containing these photographs in a drawer of a bedside table in an abandoned SS barracks while she was recovering from typhus.

In the album, Lili Jacob first found a photograph of her rabbi but then also discovered a photo of herself, many of her neighbors, and relatives, including a famous shot of her two younger brothers Yisrael and Zelig Jacob. She brought the original album with her when she immigrated to the United States. Later published many times, these images went into evidence at the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial (in which Lili Jacob testified and in which Karl Höcker was a defendant). In 1983, Lili Jacob donated the album of photographs of her transport's arrival in Auschwitz to Yad Vashem.

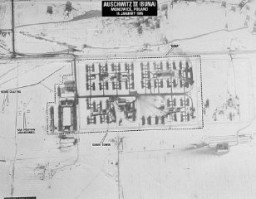

We don't know why the album that Lili discovered was created; possibly, the original owner was Richard Baer, Höcker's superior. Baer was not only the commandant of Auschwitz when the Hungarian Jews arrived but also the commander of Dora-Mittelbau, where the album was discovered. Nevertheless, it is critically important to view the two albums side by side, because they allow us to witness how the SS created two alternative views of reality. What is most striking about Höcker's Auschwitz album is that there are no photographs of prisoners, not even lurking in the background of the photos taken inside Auschwitz itself.

Though Höcker's album does not depict any criminal or immoral actions, one is struck by the amorality of the album. His album contains no photographs of gas chambers, torture chambers or even forced labor. Instead it captures SS officers going about their business, socializing, enjoying the beautiful weather and mourning fallen comrades, seemingly oblivious to the magnitude of the crimes which they are either perpetrating or enabling.

Series: Auschwitz Through the Lens of the SS

Series: Auschwitz

Switch Series

Critical Thinking Questions

- <p>Why do militaries and individuals document their activities?</p>

- <p>To what degree was the local population aware of this camp, its purpose, and the conditions within? How would you begin to research this question?</p>

- <p>Did the outside world have any knowledge about these camps? If so, what, if any, actions were taken by other governments and their officials?</p>

- <p>How does the example of this camp demonstrate the complexity and the systematic nature of the German efforts to abuse and kill the Jews?</p>