Zdziecioł (Zhetel)

As the Nazis conducted the Holocaust, they established over 1,150 ghettos throughout German-occupied eastern Europe. Among them was Zdzieciol (Zhetel).

A Project of the Miles Lerman Center

Zdziecioł is located 146 kilometers (91 miles) southwest of Minsk.

- Pre–1939: Zdziecioł (Yiddish: Zhetel), town in the Nowogródek province, Poland

- 1939–41: Dyatlovo, Belorussian SSR

- 1941–44: Djatlowo, Rayon center, Gebiet Nowogrodek, Generalkommissariat Weissruthenien

- Post-1944: Dyatlovo, Grodno province, Belorussian SSR

- Since 1991: Republic of Belarus

Jews first settled in Zdzieciol (located in present-day Belarus) in 1580. The town was the birthplace of Jacob of Dubno (the “Dubner Maggid”) and Israel Meir ha-Kohen (the “Hafetz Hayyim”). In 1897 the Jewish population was 3,979 (75 percent of the total). In 1926 there were 3,450 Jews out of 4,600 people in Zdzieciol (also 75 percent). Many Jewish refugees arrived from western and central Poland in 1939–1941 after the beginning of World War II, so that by the time of the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Jewish population of the town had increased to more than 4,500.

German forces occupied the town on June 30, 1941. On July 14, the local military commandant (Ortskommandant) ordered the Jews to wear a six-pointed yellow star on the front and the back of their clothing. On July 15, the Germans arrested 6 Jews and took them to Nowojelnia, where they killed them on the pretext that they had previously worked for the Soviet authorities. Among the victims were Etl Ovsievitz, her daughter Dina, Shimon Leveranchik, Avraham Guzovski, and Judl Bielski. On July 23, about 120 of the most respectable citizens and members of the intelligentsia were selected from among all the Jews assembled in the square. The selection was carried out according to a list compiled by SS men who had arrived in Zdziecioł. Among those arrested were Alter Dvoretzky and the rabbi. The local Jews bribed the Germans and attained the release of Dvoretzky and the rabbi. All the others were allegedly taken for forced labor, but two days later it was discovered that they had been murdered in the forest near the military barracks in Nowogródek. According to Abram Kaplan—the only Jew presently living in the Zdziecioł area—the remaining Jews then had to perform a variety of different jobs. Some worked as cleaners for the local administration, and many others worked for farmers in the surrounding villages. On October 1, 1941, all the Jews living in Zdziecioł were registered.

At the end of August 1941, authority was transferred to the civil administration, At this time a Judenrat was formed, with Shmuel Kustin as the chairman and Alter Dvoretzky as his deputy. Soon afterwards, Dvoretzky replaced Kustin as chairman. Dvoretzky was 37 and had been educated as a lawyer in Berlin and Warsaw.1

One of the main tasks of the Judenrat was to ensure that all German orders were strictly implemented. On the second day of Sukkot, some Germans arrived in Zdziecioł to requisition horses for the army. Many of the Jews decided to hide, but the Germans caught one, Jaakov Noa, and shot him. On November 28, 1941, the Jews of Zdziecioł were made to line up and forced to surrender all their valuables to the Germans. Libe Gercowski, accused of having hidden two gold rings, was selected and shot in front of everyone. On that day the Judenrat was also obliged to provide four glaziers and 15 carpenters who were sent to an unknown destination. On December 15, 1941, 400 men were sent to the labor camp in Dworzec to perform construction work at the airfield for the Organisation Todt (OT). On December 25, 1941, the German authorities ordered the Jews to surrender all their fur coats.

Alter Dvoretzky established links with the Jews living in the surrounding villages and with a group of former Red Army soldiers who were organizing a partisan force in the area. In the fall of 1941, before the ghetto was set up, Dvoretzky himself formed a Jewish underground, consisting of about 60 people. This organization was divided into 20 cells, each with 3 members. They obtained some weapons about a month before the ghetto was established. About 10 underground members were in the Jewish Police.2

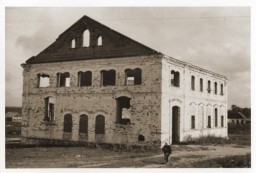

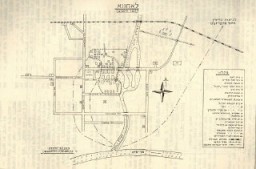

On February 22, 1942, the authorities put up posters announcing that the Jews had to move into the ghetto, which was based around the synagogue and the Talmud Torah building.3 According to Peretz Bousel, two Jewish families were exempted from the requirement to move into the ghetto: the families of Ben Zion Paskovsky and Betzalel Bousel, who in 1939 had owned a leather factory. Jews were also moved into the ghetto from other nearby Jewish communities, including Bielica.4

There was no detailed plan for the resettlement of the Jews into their new living quarters. Five or six families had to share each house, and many families were split up. Eight or more people lived in each room, with the furniture removed and replaced by improvised bunk beds. Some families, like the Kaplans, prepared secret hiding places in the ghetto, which helped them survive the massacre.

The ghetto was partly fenced by wood and barbed wire, and two local policemen guarded the gate. The Jews were not even permitted to talk to other citizens and could be shot if they attempted to obtain food from the outside. Nevertheless, peasants still brought food to the ghetto to exchange for gold, clothes, and other items. Special work permits were issued to those working outside the ghetto. The Jews were guarded when marching in and out of the ghetto in columns to perform forced labor.5

Upon moving into the ghetto, the underground headed by Dvoretzky had the following aims: to prepare for armed revolt if the liquidation of the ghetto was imminent; to collect money to buy weapons and bring them into the ghetto; and to try to persuade the local Christian population not to cooperate with the Germans.6

The group made contact with the local leader of the Soviet partisans, Nikolai Vakhonin. A number of Jews who had fled from Zdziecioł, Yołudek, Bielica, Kozłowszczyzna, Dworzec, and Nowogródek were known to be hiding in the Lipichanski Forest. Pinya Green and Hershl Kaplinski were their leaders. On April 20, 1942, Dvoretzky and six members of the ghetto underground were forced to escape to the forest after their organization became known to the Germans. Unfortunately Dvoretzky was killed in an ambush by non-Jewish partisans shortly afterwards.7

After a while, a partisan detachment of more than 100 Jews was formed in the forest near Zdziecioł, known as the “Zheteler detachment.” Anyone who wanted to join the partisans first had to obtain a gun. The unit was divided into three platoons, headed by Hershl Kaplinski, Jonah Midvetsky, and Shalom Ogulnik. The battalion also included women, acting as nurses, cooks, secretaries, typists, and washerwomen. A few of them also took part in combat activities.

The unit’s base was some 20 kilometers (12.4 miles) from Zdziecioł in the Lipichanski Forest. Its members coordinated their activities with other Soviet partisans operating there, in particular with the Orlanski detachment (renamed “Bor’ba” [Struggle] on January 5, 1943, commanded by Nikolai Vakhonin) and the Lenin brigade. The partisans attacked the railroad tracks on the Lida to Minsk line and the Wołkowysk to Białystok line. Yisrael Bousel invented a fastacting mine, which the partisans used to derail German trains. He was posthumously awarded the title “Hero of the Soviet Union.”

On April 29, 1942, the Germans arrested the Judenrat, and at dawn on April 30, the ghetto inmates woke to shots inside the ghetto. The Germans announced through the Judenrat that all the Jews were to go to the old cemetery, situated inside the ghetto. At this time the Germans and their collaborators began driving the Jews out of their houses, beating, kicking, and shooting those who were reluctant to obey. The Gebietskommissar conducted a selection, and more than 1,000 Jews, composed mainly of women, children, and the elderly, were escorted into the Kurpyash Forest south of the town, where pits had been prepared. There, the Germans shot them in groups of 20. The massacre was conducted by German and local Polish police forces.

The second massacre started on August 6, 1942, and lasted for three days, as many Jews hid in prepared bunkers. During the liquidation of the ghetto, 2,000 to 3,000 Jews were shot and buried in three mass graves in the Jewish cemetery, with roughly 1,000 victims in each grave. Slightly more than 200 Jewish craftsmen were transferred to the ghetto in Nowogródek. 8 This was the end of the ghetto and of the Jewish community of Zdziecioł. Several hundred Jews, who had hidden, fled after the massacre; some formed a family camp in the Nakryshki Forest, where they survived until liberation.

Word of the “Zhetel partisan detachment” spread among Jews in the labor camps of Dworzec and Nowogródek, and a number of Jews tried to join them. Many were caught on the way to the forest. The Zheteler detachment also took revenge on local collaborators. For example, in the village of Molery on September 10, 1942, after eliminating two collaborators, the Jewish partisans informed the village elder of the reasons for this reprisal.

Sources

The yizkor book of Baruch Kaplinski, ed., Pinkes Zshetl (Tel Aviv: Zetel Association in Israel, 1957), containsmuch information on the town but refers only briefly to the Holocaust period. A recent Israeli publication by Haya Lipski, Rivkah Lipski-Kaufman, and Yitshak Ganoz, eds., ‘Ayaratenu Z’etel: Shishim shanah le-hurban kehilat Z’etel 1942– 2002 (Tel Aviv: Irgun yots’e Z’etel be- Yisrael, 2002), deals with the fate of the town’s Jews. In Pamiats’. Diatlovo raion (Minsk, 1997), there is a list of the Jews murdered in 1942. An article on the Holocaust in Diatlovo raion was published in Moj Rodny Kut, no. 2 ( July 2002). Regarding the underground and the partisans, there is a memoir by Shalom Gerling, Korot Lochem Yehudi (Lohamei Hagetaot, 1968). Additional information can be found in Shalom Cholawsky, The Jews of Bielorussia during World War II (Amsterdam: Harwood, 1998); and Israel Gutman, ed., Enzyklopädie des Holocaust: Die Verfolgung und Ermordung der europäischen Juden (Berlin: Argon, 1993), 1:354–355.

Documentation regarding the fate of the Jews of Zdziecioł can be found in the following archives: BA-L (B 162/3452- 59); NARB (845- 1- 186, pp. 37–38); USHMM (RG- 50.030*0332); and YVA (e.g., M-1/E/457).

Series: Resistance in the Smaller Ghettos of Eastern Europe

Critical Thinking Questions

- Why did the Nazis implement a system of ghettos?

- Learn about the lives of the Jews in the community of Zdziecioł before 1939.

Further Reading

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. 2, Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe, ed. Martin Dean. Bloomington: Indiana University Press in association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2012.

Gerling, Korot Lochem Yehudi, p. 47.

Gerling, Korot Lochem Yehudi, p. 47.

See oral history of Sonia Heidocosky Zissman, USHMM, RG-50.030*0332, p. 9 of transcript. The Soviet Extraordinary State Commission (ChGK) report, however, states that the ghetto was set up in 1941 and held up to 4,500 people; see NARB, 845-1-186, pp. 37–38.

L. Losh, ed., Book of Belitzah (Bielica) (Tel Aviv: Belitzah Landmannschaft Organizations in Israel and the U.S., 1965), p. 347.

NARB, 845- 1- 186, pp. 37– 38.

Kaplinski, Pinkes Zshetl, pp. 369– 370.

Kaplinski, Pinkes Zshetl, pp. 47, 60– 63.

See USHMM, RG- 50.030*0332; BA-L, B 162/3453 (202 AR- Z 94e/59), pp. 329– 333; and YVA, M-1/E/457 (Shmariahu Furmanski). The ChGK dates the second massacre in July 1942 and estimates the total of Jewish victims at 3,500. The names of 1,601 victims have been established; see NARB, 845-1-186, pp. 37–38.