Nuremberg Race Laws

The Nuremberg Race Laws were two in a series of key decrees, legislative acts, and case law in the gradual process by which the Nazi leadership moved Germany from a democracy to a dictatorship.

Background

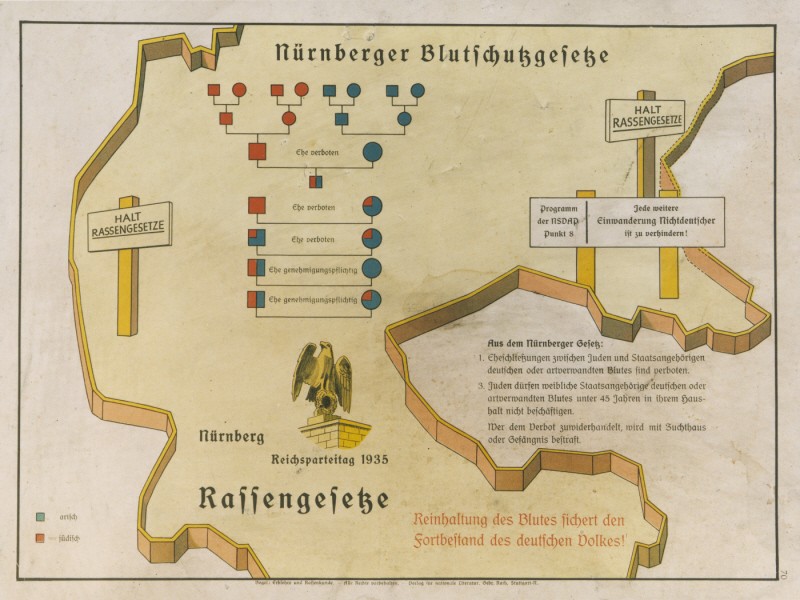

Two distinct laws passed in Nazi Germany in September 1935 are known collectively as the Nuremberg Laws: the Reich Citizenship Law and the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor. These laws embodied many of the racial theories underpinning Nazi ideology. They would provide the legal framework for the systematic persecution of Jews in Germany.

Two distinct laws passed in Nazi Germany in September 1935 are known collectively as the Nuremberg Laws: the Reich Citizenship Law and the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor. These laws embodied many of the racial theories underpinning Nazi ideology. They would provide the legal framework for the systematic persecution of Jews in Germany.

Adolf Hitler announced the Nuremberg Laws on September 15, 1935. Germany’s parliament (the Reichstag), then made up entirely of Nazi representatives, passed the laws. Antisemitism was of central importance to the Nazi Party, so Hitler had called parliament into a special session at the annual Nazi Party rally in Nuremberg, Germany.

Reich Citizenship Law

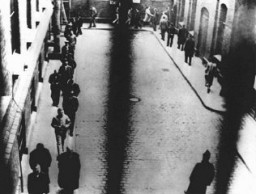

The Nazis had long sought a legal definition that identified Jews not by religious affiliation but according to racial antisemitism. Jews in Germany were not easy to identify by sight. Many had given up traditional practices and appearances and had integrated into the mainstream of society. Some no longer practiced Judaism and had even begun celebrating Christian holidays, especially Christmas, with their non-Jewish neighbors. Many more had married Christians or converted to Christianity.

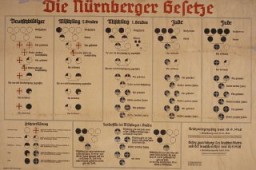

According to the Reich Citizenship Law and many ancillary decrees on its implementation, only people of “German or kindred blood” could be citizens of Germany. A supplementary decree published on November 14, the day the law went into force, defined who was and was not a Jew. The Nazis rejected the traditional view of Jews as members of a religious or cultural community. They claimed instead that Jews were a race defined by birth and by blood.

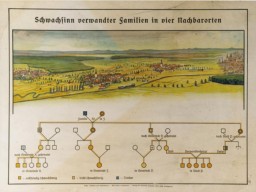

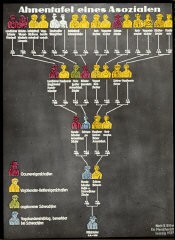

Despite the persistent claims of Nazi ideology, there was no scientifically valid basis to define Jews as a race. Nazi legislators looked therefore to family genealogy to define race. People with three or more grandparents born into the Jewish religious community were Jews by law. Grandparents born into a Jewish religious community were considered “racially” Jewish. Their “racial” status passed to their children and grandchildren. Under the law, Jews in Germany were not citizens but “subjects" of the state.

This legal definition of a Jew in Germany covered tens of thousands of people who did not think of themselves as Jews or who had neither religious nor cultural ties to the Jewish community. For example, it defined people who had converted to Christianity from Judaism as Jews. It also defined as Jews people born to parents or grandparents who had converted to Christianity. The law stripped them all of their German citizenship and deprived them of basic rights.

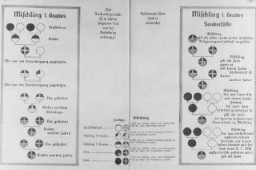

To further complicate the definitions, there were also people living in Germany who were defined under the Nuremberg Laws as neither German nor Jew, that is, people having only one or two grandparents born into the Jewish religious community. These “mixed-raced” individuals were known as Mischlinge. They enjoyed the same rights as “racial” Germans, but these rights were continuously curtailed through subsequent legislation.

Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor

The second Nuremberg Law, the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor, banned marriage between Jews and non-Jewish Germans. It also criminalized sexual relations between them. These relationships were labeled as “race defilement” (Rassenschande).

The law also forbade Jews to employ female German maids under the age of 45, assuming that Jewish men would force such maids into committing race defilement. Thousands of people were convicted or simply disappeared into concentration camps for race defilement.

Significance of the Nuremberg Laws

The Nuremberg Laws reversed the process of emancipation, whereby Jews in Germany were included as full members of society and equal citizens of the country. More significantly they laid the foundation for future antisemitic measures by legally distinguishing between German and Jew. For the first time in history, Jews faced persecution not for what they believed, but for who they—or their parents—were by birth. In Nazi Germany, no profession of belief and no act or statement could convert a Jew into a German. Many Germans who had never practiced Judaism or who had not done so for years found themselves caught in the grip of Nazi terror.

While the Nuremberg Laws specifically mentioned only Jews, the laws eventually extended to Black people and Roma and Sinti (Gypsies) living in Germany. The definition of Jews, Black people, and Roma as racial aliens facilitated their persecution in Germany.

During World War II, many countries allied to or dependent on Germany enacted their own versions of the Nuremberg Laws. By 1941, Italy, Hungary, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Vichy France, and Croatia had all enacted anti-Jewish legislation similar to the Nuremberg Laws in Germany.

Translation

Reich Citizenship Law of September 15, 1935

(Translated from Reichsgesetzblatt I, 1935, p. 1146.)

The Reichstag has unanimously enacted the following law, which is promulgated herewith:

Article 1

1. A subject of the state is a person who enjoys the protection of the German Reich and who in consequence has specific obligations toward it.

2. The status of subject of the state is acquired in accordance with the provisions of the Reich and the Reich Citizenship Law.

Article 2

1. A Reich citizen is a subject of the state who is of German or related blood, and proves by his conduct that he is willing and fit to faithfully serve the German people and Reich.

2. Reich citizenship is acquired through the granting of a Reich citizenship certificate.

3. The Reich citizen is the sole bearer of full political rights in accordance with the law.

Article 3

The Reich Minister of the Interior, in coordination with the Deputy of the Führer, will issue the legal and administrative orders required to implement and complete this law.

Nuremberg, September 15, 1935

At the Reich Party Congress of Freedom

The Führer and Reich Chancellor

[signed] Adolf Hitler

The Reich Minister of the Interior

[signed] Frick

Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor of September 15, 1935

(Translated from Reichsgesetzblatt I, 1935, pp. 1146-7.)

Moved by the understanding that purity of German blood is the essential condition for the continued existence of the German people, and inspired by the inflexible determination to ensure the existence of the German nation for all time, the Reichstag has unanimously adopted the following law, which is promulgated herewith:

Article 1

1. Marriages between Jews and citizens of German or related blood are forbidden. Marriages nevertheless concluded are invalid, even if concluded abroad to circumvent this law.

2. Annulment proceedings can be initiated only by the state prosecutor.

Article 2

Extramarital relations between Jews and citizens of German or related blood are forbidden.

Article 3

Jews may not employ in their households female subjects of the state of Germany or related blood who are under 45 years old.

Article 4

1. Jews are forbidden to fly the Reich or national flag or display Reich colors.

2. They are, on the other hand, permitted to display the Jewish colors. The exercise of this right is protected by the state.

Article 5

1. Any person who violates the prohibition under Article 1 will be punished with a prison sentence with hard labor.

2. A male who violates the prohibition under Article 2 will be punished with a jail term or a prison sentence with hard labor.

3. Any person violating the provisions under Articles 3 or 4 will be punished with a jail term of up to one year and a fine, or with one or the other of these penalties.

Article 6

The Reich Minister of the Interior, in coordination with the Deputy of the Führer and the Reich Minister of Justice, will issue the legal and administrative regulations required to implement and complete this law.

Article 7

The law takes effect on the day following promulgation, except for Article 3, which goes into force on January 1, 1936.

Nuremberg, September 15, 1935

At the Reich Party Congress of Freedom

The Führer and Reich Chancellor

[signed] Adolf Hitler

The Reich Minister of the Interior

[signed] Frick

The Reich Minister of Justice

[signed] Dr. Gürtner

The Deputy of the Führer

[signed] R. Hess

Series: Nazi Racism

Series: Law, Justice, and the Holocaust

Switch Series

Critical Thinking Questions

- <p>Since the Nazis could never prove a biological, or racial, basis for Judaism, how did they define Jews in these laws? What questions does this raise?</p>

- <p>What privileges and protections of German citizenship were now lost to those who were defined as Jewish?</p>

- <p>How can knowledge of the Nuremberg Laws help citizens today respond to threats of genocide and mass atrocity in the world?</p>