Deadly Medicine: Creating the Master Race

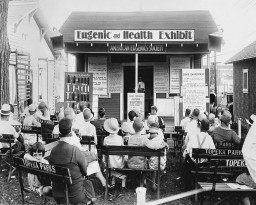

The Nazi regime under Adolf Hitler aimed to purify the genetic makeup of the population through measures known as racial hygiene or eugenics. Scientists in the biomedical fields, many of them medically trained experts, played a role in legitimizing these policies and helping to implement them.

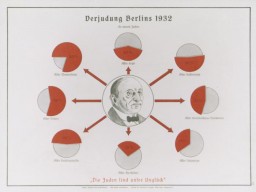

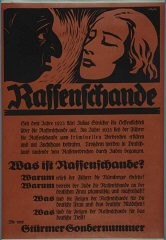

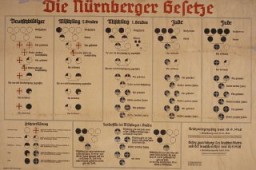

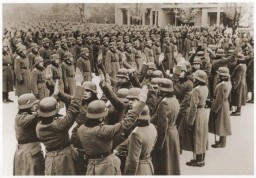

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany’s government led by Adolf Hitler promoted a nationalism that combined territorial expansion, claims of the biological superiority of an "Aryan master race," and virulent antisemitism. Driven by a racist ideology legitimized by German scientists, the Nazis attempted to eliminate all of Europe’s Jews, ultimately killing six million in the Holocaust. Many other people also became victims of persecution and murder in the Nazis’ campaign to cleanse German society of individuals viewed as threats to the "health" of the nation.

Our starting point is not the individual, and we do not subscribe to the view that one should feed the hungry, give drink to the thirsty, or clothe the naked....Our objectives are entirely different: we must have a healthy people in order to prevail in the world.

—Joseph Goebbels, Minister of Propaganda, 1938

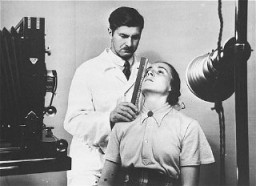

The Nazi regime under Adolf Hitler aimed to purify the genetic makeup of the population through measures known as racial hygiene or eugenics. Scientists in the biomedical fields—especially anthropologists, psychiatrists, and geneticists, many of them medically trained experts—played a role in legitimizing these policies and helping to implement them. They had embraced these ideas before Hitler took power in 1933 and they would welcome the regime because of its support of eugenics and its support of their research.

When Nazi racial hygiene was implemented, the categories of persons and groups regarded as biologically threatening to the health of the nation were greatly expanded. These categories included Jews, Roma (Gypsies), people with physical and mental disabilities, and other minorities.

Ultimately, Nazi racial hygiene policies culminated in the Holocaust. Under cover of World War II, and using the war as a pretext, Nazi racial hygiene was radicalized. There was a shift from controlling reproduction and marriage to eliminating persons regarded as biological threats.

Medical Professionals

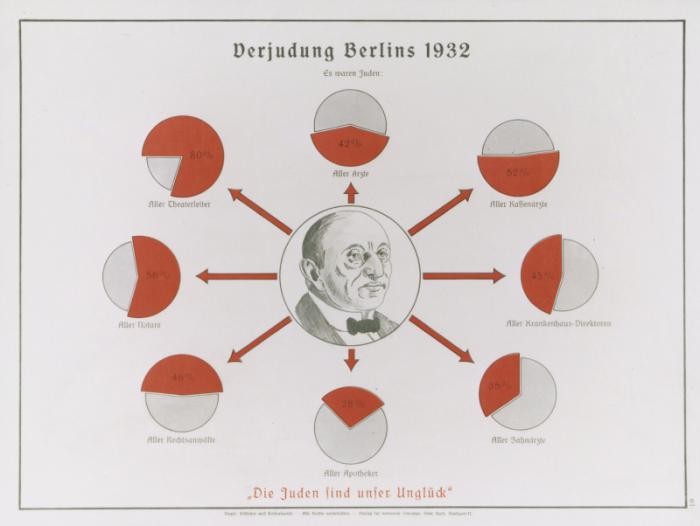

Physicians were drawn disproportionately to Nazism due to overcrowding in the profession aggravated by economic depression, and as a backlash to the relatively high proportion of Jews in medical practice ( in 1933, 11 percent of all German physicians).

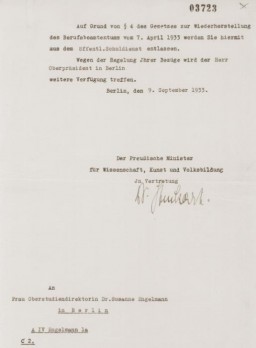

Many medical professionals applauded the barring of Jewish doctors from state-run clinics and hospitals and later measures preventing Jewish doctors from practicing. Welcoming the Nazi regime's emphasis on biology and heredity, German physicians helped carry out Nazi eugenic racial policies aimed at increasing the births of hereditary healthy "German-blooded" persons and decreasing those of persons viewed as genetically "defective" and a burden on national resources. Family physicians helped identify candidates for forced sterilization. Doctors and other medical personnel carried out the approximately 400,000 sterilization procedures.

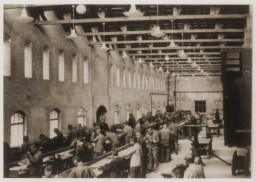

After World War II began and Nazi policies escalated to killing, physicians and nurses became perpetrators in the murder of children and adults deemed "incurably ill." Many of the medical personnel in the "euthanasia," or T4, program for the clandestine murder of institutionalized Germans (mostly non-Jews) by gassing were screened for ideological beliefs and political loyalty. After 1942, in a more decentralized format, patients were killed by lethal overdose and starvation. Now hundreds of less ideologically committed asylum directors, pediatricians, psychiatrists, family doctors, and nurses participated in the crimes to varying degrees. Many proponents of eugenics who had earlier rejected killing as part of their program did, however, come to support murders "for the good of the Fatherland" during the "national emergency of war."

Series: Deadly Medicine

Series: The Role of German Professionals and Civil Leaders

Switch Series

Critical Thinking Questions

- What is the appropriate relationship between a government and the medical profession?

- What is the appropriate relationship between ideology and the medical profession?

- How can knowledge of the events in Germany and Europe before the Nazis came to power help citizens today respond to threats of genocide and mass atrocity in the world?