War Refugee Board: Activities

On January 22, 1944, President Franklin D. Roosevelt announced a new policy to rescue and provide relief for Jews and other groups persecuted by Nazi Germany and its collaborators. The War Refugee Board, tasked with carrying out these programs, likely saved tens of thousands of lives.

-

1

The War Refugee Board, headed by the secretaries of State, War, and Treasury, operated between January 22, 1944 and September 15, 1945. Most of the staff were Treasury Department employees.

-

2

The War Refugee Board streamlined the work of private relief agencies, helping them send money and resources into neutral and enemy territory. They also placed American representatives in neutral nations to supervise projects and pressure these countries to welcome refugees.

-

3

The War Refugee Board was the first and only official American response to the crimes we now call the Holocaust. Winning World War II, however, remained the Allied priority.

Relief Funding

One of the most important functions of the War Refugee Board (WRB) was to streamline the process for sending money overseas for relief purposes. In 1943, discussions between the State and Treasury departments about a World Jewish Congress rescue and relief proposal had taken months. The creation of the WRB meant that licenses (official permissions) for similar projects could instead be issued in a matter of weeks.

The WRB assisted in sending about $12,000,000 overseas to fund relief projects, ranging from supplying food packages for concentration camp prisoners to funding underground movements in occupied countries. Organizations like the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, the Va'ad ha-Hatsala, and the World Jewish Congress could now send money overseas to provide on-the-ground aid and assistance.

Diplomatic Work

Some of the WRB's work was diplomatic and could be conducted from Washington. The WRB staff pressured neutral countries to accept greater numbers of refugees, and to protest the persecution of Jews and other victims.

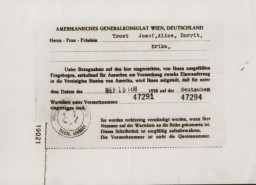

In the spring of 1944, the agency sent requests to Central and South American governments, asking them to agree to give protection to any person who held documents claiming citizenship of their respective nations. For example, if a person in Hungary had Salvadoran papers, El Salvador agreed to inform Germany through diplomatic channels that this was a Salvadoran citizen and would be eligible for diplomatic prisoner exchanges. The WRB believed that thousands of people were saved who were able to claim status as citizens or under the protection of Central and South American nations, even when their papers were invalid or forged.

Intelligence Information and Local Negotiations

The WRB also appointed overseas representatives in Sweden, Switzerland, the Mediterranean (which encompassed North Africa and Italy), Turkey, Portugal, and Great Britain. These representatives, many of whom were either from the Treasury department or had backgrounds with relief organizations, provided important intelligence information and were able to negotiate on the ground with Jewish organizations, local government officials, and other diplomats.

For example, Ira Hirschmann, the WRB representative in Turkey, worked to get refugees from Romania to Palestine. This involved purchasing boats to carry the refugees, negotiating with Romania to let the refugees leave, with Turkey to let the ships land and provide transit by train for the refugees, and with Great Britain to admit the refugees into Palestine. As a result of the negotiations, about 8,000 refugees were able to reach Palestine safely, though one ship, the Mefkure, was tragically torpedoed at sea.

Encouraging Safe Havens for Refugees

The WRB constantly encouraged the neutral nations of Europe to keep their borders open to any refugee who was able to escape occupied territory. They feared, though, that the United States would be accused of not providing a safe haven for refugees. In June 1944, President Franklin D. Roosevelt announced the formation of the Fort Ontario Emergency Refugee Shelter in Oswego, New York. Nearly 1,000 men, women, and children, the majority of them Jewish, came from Allied-occupied Italy to live at Fort Ontario in August 1944.

Because the refugees entered the United States outside of legal immigration quotas, however, their status was uncertain. Though some of the children attended local public schools, US officials prevented the refugees from leaving the shelter for extended periods. Since many of the refugees had family already in the United States, they resisted repatriation to Europe after the war. When Fort Ontario closed in February 1946 (five months after the WRB dissolved), the US government finally admitted the refugees as immigrants.

Raoul Wallenberg

The Germans occupied Hungary in March 1944. Shortly after Hungarian authorities began to deport hundreds of thousands of Hungarian Jews, the WRB learned of the massive deportations to the killing center at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Unable to place a US representative in Budapest (since the United States was at war with Hungary, a German ally), the WRB received assistance from the Swedish government. Through its representative in Stockholm, Iver Olsen, the WRB recruited businessman Raoul Wallenberg and the Swedish Foreign Ministry assigned him to the Swedish legation in Budapest.

Wallenberg arrived in Budapest on July 9, 1944—the day the last deportation train left Hungary for Auschwitz-Birkenau—and assumed his post as third secretary at the Swedish legation. With WRB funds, he distributed certificates of protection to thousands of Jews, effectively preventing their deportation from Budapest. He intervened many times to secure the release of Jews claiming Swedish protection and worked tirelessly to save as many Jews as possible.

Working together with other neutral legations in Budapest, in particular the Swiss legation and Carl Lutz, Wallenberg was at the center of the largest and most direct rescue operation undertaken by the WRB and is credited saving the lives of thousands of Jews.

Wallenberg was last seen in the company of Soviet officials in January 1945. Believing him to be a US intelligence agent, Soviet authorities took him to the Soviet Union. Details surrounding Wallenberg's death may never be clarified. In October 2016, 71 years after his disappearance, Swedish officials formally declared Wallenberg legally dead.

Reviewing Proposals Calling for Military Actions

The WRB received many suggestions for relief and rescue from various foreign and domestic organizations as well as from concerned US citizens. Some proposals called for specific Allied military actions to halt or slow the mass murder of Europe's Jews. These included urging the underground resistance movements in German-occupied Europe to rescue Jews, arming Jews for self-defense against the Germans and their allies and collaborators, hiding Jews or smuggling them out to safety, bombing the rail lines leading from Hungary to the Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center, and destroying the gas chambers at Auschwitz-Birkenau, or the entire camp, by either aerial bombardment or ground attacks by the Polish underground or Allied paratroopers.

The WRB was generally hesitant to officially endorse plans calling for the use of Allied military forces for rescue or bombing operations. The WRB was mandated only to undertake relief and rescue projects “consistent with the successful prosecution of the war,” so they were unable to order the diversion of military resources. Among Jewish organizations, opinions differed on what military solutions to support. Some believed that the bombing of the gas chambers would stop the killings and save lives, while others vehemently opposed it, fearing that many Jewish prisoners in Auschwitz would be killed. Still others wondered whether such a plan would actually prevent Jewish deaths.

On November 8, 1944, WRB director John Pehle, after reading the translated eyewitness reports of the killings in Auschwitz, overcame his initial qualms and strongly urged the US War Department to have the gas chambers bombed. Just six days earlier, on November 2, on orders of SS chief Heinrich Himmler the gassing facilities at Auschwitz-Birkenau were used for the last time. After reviewing Pehle's proposal, the War Department again responded that the plan was not feasible and would divert Allied strategic air forces from vital military targets, arguing that the best way to save lives at Auschwitz would be to defeat Nazi Germany as quickly as possible.

Conclusion

In the WRB's final report, written in September 1945, the staff wrote that “the accomplishments of the Board cannot be evaluated in terms of exact statistics, but it is clear, however, that hundreds of thousands of persons as well as the tens of thousands who were rescued through activities organized by the Board, continued to live and resist as a result of its vigorous and unremitting efforts.”

The War Refugee Board was a significant attempt to rescue and relieve Jews and other endangered people under German occupation. Though not created until 1944, the establishment of the WRB provided a clear and coherent US rescue policy. After the war, many, including John Pehle (the board's first director), referred to the accomplishments of the WRB as “little and late.” The establishment of the WRB was late, and there is no way to know how many lives might have been saved had it been created earlier. But for those the WRB did save, and for the thousands aided through the relief work the WRB facilitated, the efforts cannot be characterized as “little.”

Series: The United States and the Holocaust

Critical Thinking Questions

- What pressures and motivations may have delayed the formation of a government program to aid the endangered Jews of Europe?

- What pressures and motivations spurred agencies and individuals to push for such a program?

- Which government agencies have programs similar to the WRB’s varied efforts to assist endangered populations today?

- What obstacles exist today to government efforts to rescue endangered populations elsewhere?