The United States and the Holocaust: Why Auschwitz was not Bombed

During the spring of 1944, the Allies received more explicit information about the process of mass murder by gassing carried out at Auschwitz-Birkenau. On some days as many as 10,000 people were murdered in its gas chambers. In desperation, Jewish organizations made various proposals to halt the extermination process and rescue Europe's remaining Jews. A few Jewish leaders called for the bombing of the Auschwitz gas chambers; others opposed it. Like some Allied officials, both sides feared the death toll or the German propaganda that might exploit any bombing of the camp's prisoners. No one was certain of the results.

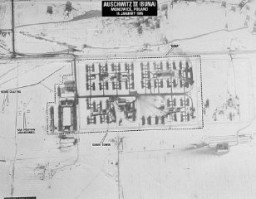

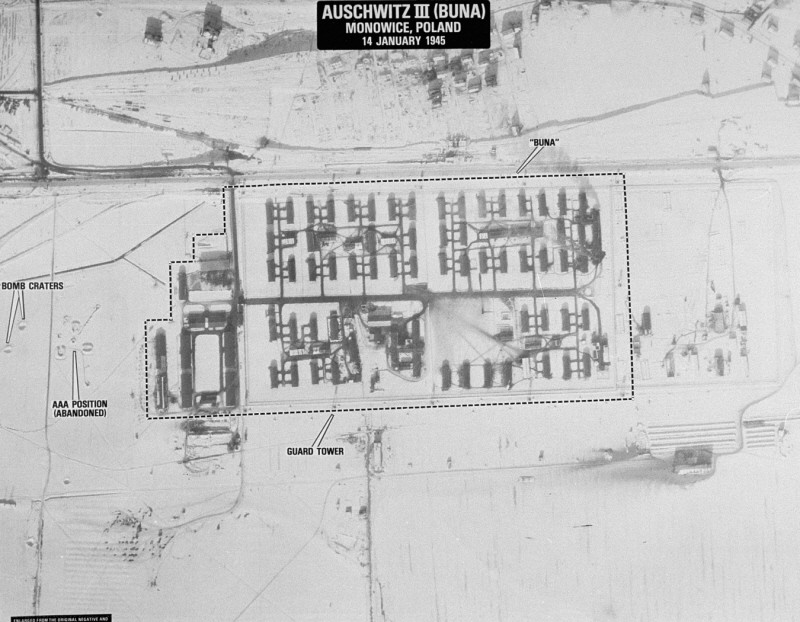

Even after Anglo-American air forces developed the capacity to hit targets in Silesia (where the Auschwitz complex was located) in July 1944, US authorities decided not to bomb Auschwitz. American officials explained this decision in part with a technical argument that their aircraft did not have the capacity to conduct air raids on such targets with sufficient accuracy, and in part with a strategic argument that the Allies were committed to bombing exclusively military targets in order to win the war as quickly as possible.

Allied bombardment of Auschwitz-Birkenau in mid-July 1944 would not have saved the approximately 310,000 Hungarian Jews whom the Germans had killed upon arrival at the killing center between May 15 and July 11, 1944. Moreover, barracks located not far from the gas chambers at Birkenau housed 51,117 prisoners (31,406 of them women and children).

In the summer and fall of 1944, the World Jewish Congress and the War Refugee Board (WRB) forwarded requests to bomb Auschwitz to the US War Department. These requests were denied. On August 14, John J. McCloy, Assistant Secretary of War, advised that “such an operation could be executed only by the diversion of considerable air support…now engaged in decisive operations elsewhere and would in any case be of such doubtful efficacy that it would not warrant the use of our resources.” Yet within a week, the US Army Air Force carried out a heavy bombing of the I.G. Farben synthetic oil and rubber (Buna) works near Auschwitz III—less than five miles from the Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center.

For prisoners in the Auschwitz complex, the bombs dropping nearby gave hope. One survivor later recalled:

“We were no longer afraid of death; at any rate not of that death. Every bomb that exploded filled us with joy and gave us new confidence in life.”

In subsequent decades, the Allied decision not to bomb the gas chambers in or the rail lines leading to Auschwitz-Birkenau has been a source of sometimes bitter debate. Proponents of bombing continue to argue that such an action, while it might have killed some prisoners, could have slowed the killing operations and perhaps ultimately saved lives.

Series: Auschwitz

Critical Thinking Questions

- What competing priorities emerged in the debate to bomb Auschwitz?

- Why does the debate about the decision not to bomb the camps still continue and resonate?

- What priorities do military officials take into account when making tactical decisions, which may involve endangering civilians?

Further Reading

Breitman, Richard, and Alan Kraut, American Refugee Policy and European Jewry, 1933-1945. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987.

Breitman, Richard, Official Secrets: What the Nazis Planned, What the British and Americans Knew. New York: Hill and Wang, 1998.

Feingold, Henry L., Bearing Witness: How America and Its Jews Responded to the Holocaust. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1995.

Gurock, Jeffrey S., ed. America, American Jews, and the Holocaust. New York: Routledge, 1998.

Hamerow, Theodor. While We Watched: Europe, America, and the Holocaust. New York: Norton, 2008.

Lipstadt, Deborah E., Beyond Belief: The American Press and the Coming of the Holocaust, 1933-1945. New York: Free Press, 1986.

Neufeld, Michael J., and Michael Berenbaum, editors. The Bombing of Auschwitz: Should the Allies Have Attempted It? New York: St. Martin's Press, 2000.

Wyman, David S. Paper Walls: America and the Refugee Crisis, 1938-1941. New York: Pantheon Books, 1985.

Wyman, David S. The Abandonment of the Jews: America and the Holocaust, 1941-1945. New York: The New Press, 1998.