Displaced Persons

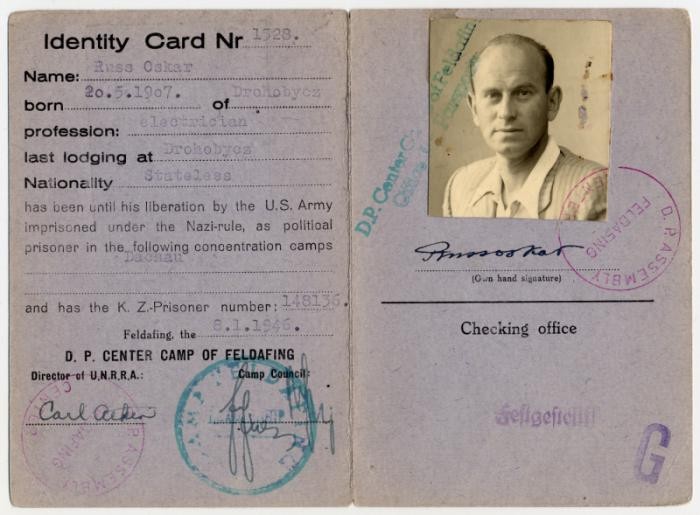

From 1945 to 1952, more than 250,000 Jewish displaced persons (DPs) lived in camps and urban centers in Germany, Austria, and Italy. These facilities were administered by Allied authorities and the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA).

Among the concerns facing these Jewish DPs in the years following the Holocaust were the problems of daily life in the displaced persons camps, Zionism, and emigration.

Daily Life

Soon after liberation, survivors began searching for their families. UNRRA established the Central Tracing Bureau to help survivors locate relatives who had survived the concentration camps. Public radio broadcasts and newspapers contained lists of survivors and their whereabouts. The attempt to reunite families went hand-in-hand with the creation of new ones; there were many weddings and many births in the DP camps.

Schools were soon established and teachers came from Israel and the United States to teach the children in the DP camps. Orthodox Judaism also began its rebirth as yeshivot (religious schools) were founded in several camps, including Bergen-Belsen, Foehrenwald, and Feldafing. Religious holidays became major occasions for gatherings and celebrations. Jewish volunteer agencies supplied religious articles for everyday and holiday use.

The DPs also transformed the camps into active cultural and social centers. Despite the often bleak conditions—many of the camps were former concentration camps and German army camps—social and occupational organizations soon abounded. Journalism sprang to life with more than 170 publications. Numerous theater and musical troupes toured the camps. Athletic clubs from various DP centers challenged each other.

Zionism

Zionism (the movement to return to the Jewish homeland in what was then British-controlled Palestine) was perhaps the most incendiary question of the Jewish DP era. In increasing numbers from 1945–48, Jewish survivors, their nationalism heightened by lack of autonomy in the camps and having few destinations available, chose British-controlled Palestine as their most desired destination. The DPs became an influential force in the Zionist cause and in the political debate about the creation of a Jewish state. They condemned British barriers to open immigration to Palestine.

Agricultural training farms and communes that prepared the DPs for the pioneering life were founded in many DP camps. Zionist youth groups instilled an affinity for Israel among the young. David Ben-Gurion, leader of the Jewish community in Palestine, visited DP camps several times in 1945 and 1946. His visits raised the DPs' morale and rallied them in support of a Jewish state. The Jewish Agency (the de facto Jewish authority in Palestine) and Jewish soldiers from the British Army's Jewish Brigade further consolidated the alliance between the DPs and the Zionists, often assisting illegal immigration attempts. Mass protests against British policy became common occurrences in the DP camps.

Emigration

After liberation, the Allies were prepared to repatriate Jewish displaced persons to their homes, but many DPs refused or felt unable to return. The Allies deliberated and procrastinated for years before resolving the emigration crisis, although some Allied officials had proposed solutions just months after liberation. Earl Harrison, in his August 1945 report to President Truman, recommended mass population transfer from Europe and resettlement in British-controlled Palestine or the United States. The report influenced President Truman to order that preference be given to DPs, especially widows and orphans, in US immigration quotas. Great Britain, however, claimed that the United States had no right to dictate British policy insofar as the admission of Jews to Palestine was concerned.

Truman alone could not raise restrictive US and British immigration quotas, but he did succeed in pressuring Great Britain into sponsoring the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry. This bi-national delegation's suggestions included the admission of 100,000 Jewish DPs to Palestine. Britain's rejection of the report strengthened the resolve of many Jews to reach Palestine and, from 1945–48, the Brihah ("escape") organization moved more than 100,000 Jews past British patrols and illegally into Palestine.

British seamen captured many of the ships used in the operations and interned the passengers in camps on the island of Cyprus. The British attack on one such ship, the Exodus 1947, attracted worldwide publicity and strengthened support for the DPs' struggle to emigrate.

On May 14, 1948, the United States and the Soviet Union recognized the State of Israel. Congress also passed the Displaced Persons Act in 1948, authorizing 200,000 DPs to enter the United States. The law's stipulations made it unfavorable at first to the Jewish DPs, but Congress amended the bill with the DP Act of 1950. By 1952, over 80,000 Jewish DPs had immigrated to the United States under the terms of the DP Act and with the aid of Jewish agencies.

With over 80,000 Jewish DPs in the United States, about 136,000 in Israel, and another 20,000 in other nations, including Canada and South Africa, the DP emigration crisis came to an end. Almost all of the DP camps were closed by 1952. The Jewish displaced persons began new lives in their new homelands around the world.

Critical Thinking Questions

- What challenges did survivors face in the DP camps?

- What challenges did the Allies face in establishing and supervising DP camps?

- What responsibilities do (or should) other nations have regarding refugees from war and genocide?