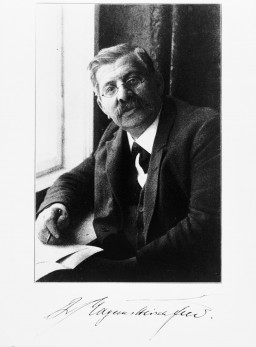

![<p>A waiter from D<span style="font-weight: 400;">ü</span>sseldorf who was arrested by the Gestapo for allegedly having sexual relations with other men. D<span style="font-weight: 400;">ü</span>esseldorf, Germany, 1938. [RW 58-61940]</p>

<p><span style="font-weight: 400;">The Nazi regime considered homosexuality a moral vice that threatened the current and future strength of the German people. They carried out a campaign against male homosexuality that included shutting down <a href="/narrative/4631">gay</a> and <a href="/narrative/6695">lesbian</a> meeting places and arresting men under <a href="/narrative/45421">Paragraph 175</a>, the statute of the German criminal code that banned sexual relations between men. </span></p>](https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/images/large/cccebf78-f2c6-4555-9381-6ac25596bb6a.jpg)

Gay Men under the Nazi Regime

The Nazi regime carried out a campaign against male homosexuality and persecuted gay men between 1933 and 1945. As part of this campaign, the Nazi regime closed gay bars and meeting places, dissolved gay associations, and shuttered gay presses. The Nazi regime also arrested and tried tens of thousands of gay men using Paragraph 175 of the German criminal code. Uncovering the histories of gay men during the Nazi era was difficult for much of the twentieth century because of continued prejudice against homosexuality and the postwar German enforcement of Paragraph 175.

-

1

Before the Nazis came to power in 1933, gay communities and networks flourished in Germany, especially in big cities. This was true despite the fact that sexual relations between men were criminalized in Germany.

-

2

Beginning in 1933, the Nazi regime harassed and dismantled Germany’s gay communities. They arrested large numbers of gay men under Paragraph 175, the statute of the German criminal code that banned sexual relations between men.

-

3

During the Nazi era, between 5,000 and 15,000 men were imprisoned in concentration camps as “homosexual” (“homosexuell”) offenders. This group of prisoners was typically required to wear a pink triangle on their camp uniforms as part of the prisoner classification system.

Introduction

The Nazi regime carried out a campaign against male homosexuality between 1933 and 1945. This campaign persecuted men who had sexual relations with other men. It is unclear how many of these men publicly or privately identified as gay or were part of gay communities and networks that had been established in Germany before the Nazi rise to power.

Beginning in 1933, the Nazi regime harassed and dismantled these communities. They also arrested large numbers of gay men under Paragraph 175. Paragraph 175 was the statute of the German criminal code that banned sexual relations between men. During the Nazi period, the police arrested about 100,000 men for allegedly violating this statute. Approximately fifty percent of these men were convicted. In some cases, this led to their imprisonment in concentration camps.

It is important to note that not all of the men arrested and convicted under Paragraph 175 identified as gay. However, any man who had sexual relations with another man faced potential arrest in Nazi Germany, regardless of how he understood his own sexuality.

Identifying as a gay man was never explicitly criminalized in Germany. However, the Nazi campaign against homosexuality and the regime’s zealous enforcement of Paragraph 175 made life in Nazi Germany dangerous for gay men.

Gay men in Germany were not a monolithic group, nor did the Nazi regime view them as such. Being gay could and often did result in persecution. However, other factors also shaped gay men’s lives during the Nazi era. Among them were supposed racial identity, political attitudes, social class, and cultural expectations about how men and women should behave (i.e., gender norms). This diversity meant that gay men had a wide range of experiences in Nazi Germany. For example, gay men active in anti-Nazi political movements risked being arrested as political opponents. And gay Jewish men faced Nazi persecution and mass murder as Jews.

Gay Men in Germany, circa 1900

Already in the mid- to late-nineteenth century, there were indications of nascent and growing gay communities in Germany. At this time, the nature of human sexuality became an area of scientific investigation and debate in Europe and the United States. Germany was at the forefront of this development, not least because of debates regarding Paragraph 175. Paragraph 175 was the statute of the German criminal code that banned sexual relations between men. It was enacted in 1871 following the unification of the German Empire and the codification of German law.

Political and social conditions in nineteenth-century Germany allowed people to publicly campaign for the decriminalization of sexual relations between men and the repeal of Paragraph 175. Eventually, individual campaigners began to organize together into groups dedicated to decriminalization. In addition to joining such groups, men who were attracted to other men also began to socialize at bars and other meeting places. These efforts helped men connect with each other and form early networks and communities.

It was in this context that some German men who were attracted to other men began to describe themselves using a new vocabulary. In addition to the older German slang phrase “warmer Bruder” (“warm brother”), some men described themselves using new words. Among these terms were “gleichgeschlechtlich” (“same-sex oriented”) and “homosexuell” (“homosexual”). The latter term dated to 1869, when a pamphlet advocating for decriminalization of sexual relations between men used the term “Homosexualität” (“homosexuality”). There were also other terms used by advocates for reform, for example, “Urning” [“Uranian,” “urning”] or “dritten Geschlecht” [“third sex”]. The newer slang word “schwul” (often translated into English as “gay”) was also increasingly popular among certain groups.

Today, the terms “Homosexualität” and “homosexuell” are often considered derogatory. At the time, however, they came into common use in Germany and beyond. These new German words were adopted into both English and French. With time, they became part of the international lexicon on sexuality. Although no longer widely accepted, these German words were early attempts to describe sexual orientation. In the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries, LGBTQ+ communities have built on, and challenged, this language.

Gay Men during the Weimar Republic (1918–1933)

Gay communities and networks in Germany continued to grow and develop during the Weimar Republic (1918–1933). This was a moment of political turmoil and economic distress, but also a time of cultural and artistic freedom. As part of the cultural and social transformations of the time, Germans publicly challenged gender and sexual norms. Sex and sexuality became points of contention in politics and culture. This was especially true in big cities such as Berlin, Cologne, Hamburg, and Frankfurt am Main.

Sex and Sexuality in the Weimar Republic

Many Germans welcomed the less restrictive social, political, and cultural climate in the Weimar Republic. Many gay men embraced this new culture. Some groups more actively and openly advocated for decriminalizing sexual relations between men. Among them were the Scientific Humanitarian Committee (Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee, WhK, established in 1897) and the League for Human Rights (Bund für Menschenrecht, BfM, established in the 1920s). Such groups cooperated with other reform-minded groups that advocated for new legal approaches to prostitution, birth control, and abortion.

But not all groups that advocated for decriminalization shared the same political perspective. For example, the German Jewish physician and sex researcher, Magnus Hirschfeld, founded the internationally renowned Institute for Sexual Science (Institut für Sexualwissenschaft) in Berlin in 1919. Hirschfeld was a pacifist and a leftist, and the Institute tended to attract people who were also left of center. The Institute conducted pioneering scientific studies and provided public education on human sexuality. It also offered various other services related to sex, including birth control and marriage counseling.

In contrast, the network of gay men that developed around author Adolf Brand and his organization Gemeinschaft der Eigenen (The Community of Kindred Spirits) took a different approach. Brand’s organization became, over time, more right-wing and nationalist. Brand and Hirschfeld agreed on the issue of decriminalization. Both men also promoted public discussions of sexuality. However, they disagreed on conceptual and political issues regarding gender and nationalism.

Not all Germans welcomed public discussions of sex. Nor did all Germans embrace the reformist agenda. Many people saw these discussions as part of the decadent, overly permissive, and immoral tendencies that they believed characterized Weimar culture. They were disturbed by the increased visibility of sex in advertising, film, and other aspects of daily life. Various right-wing and centrist political groups, as well as mainstream religious organizations, sought to promote their own version of German culture. This version was rooted in traditional music and literature, religion, and the family. In some cases, these groups blamed Jews and Communists for corrupting German culture. For example, Hirschfeld came under attack from many of these groups because of his open discussions of sexuality, his Jewish background, and his leftist political opinions.

Gay Communities and Networks in the Weimar Republic

It was in the relatively freeing atmosphere of the Weimar Republic that gay communities and networks grew and developed in unprecedented ways. More German men chose to live openly as gay. Some joined “friendship leagues” (Freundschaftsverbände), groups that politically and socially organized gay men, lesbian women, and others. Gay men gathered together at meeting places, such as bars, that catered to a gay clientele. The most famous of these was the Eldorado in Berlin.

Gay newspapers and journals, such as Die Freundschaft (Friendship) and Der Eigene (translated variously, but in this context implying “his own man”), contributed to the growth of gay networks. These publications educated readers about sexuality and published poems and short stories. They actively tried to build a sense of community among gay men, and included personal ads and information about gay meeting places. In bigger cities, readers could purchase these journals at newsstands. Throughout Germany, readers could subscribe to them by mail.

In general, gay communities were more accepted in Germany’s major cities. Smaller towns and rural areas tended to be less accepting. In Berlin, the gay community was particularly prominent. But even in bigger cities, such as Munich, gay communities were not always welcome.

Nazi Attitudes and the Case of Ernst Röhm

Before coming to power, Adolf Hitler and many other Nazi leaders condemned Weimar culture as decadent and degenerate. Part of this condemnation was a rejection of the era’s open expressions of sexuality, including the visibility of gay communities. Some prominent Nazis, including Alfred Rosenberg and Heinrich Himmler, were clearly homophobic. However, Hitler and other Nazi leaders rarely spoke publicly about homosexuality. In fact, it was not part of the 1920 Nazi Party platform, which focused on such issues as the creation of a Greater German state, the Jews, and the economy.

In terms of legal policy relating to the German criminal code, the Nazi Party opposed efforts to decriminalize sexual relations between men and repeal Paragraph 175. During parliamentary debates, Nazis claimed that sexual relations between men were a destructive vice that would lead to the ruin of the German people. They asserted these relations should be even more severely punished than current German law allowed.

But some leaders, as well as rank and file members, of the Nazi Party held attitudes that were more varied and ambivalent. There were known gay men in the Nazi movement, most notably Ernst Röhm. Röhm used the word “gleichgeschlechtlich,” same-sex oriented, to describe himself. He was the leader of the SA (Sturmabteilung, commonly called Stormtroopers), a violent and radical Nazi paramilitary.

For Röhm, his sexuality did not conflict with Nazi ideology or compromise his role as SA leader. In Röhm’s understanding, legalizing sexual relations between men was not about encouraging liberal democratic rights or tolerance. Rather, he believed it was about the overthrow of mainstream morality. Röhm wrote that the “prudery” of some of his fellow Nazis “does not seem revolutionary to me.”

Röhm’s sexuality was an open secret in the Nazi Party that turned into a public scandal in 1931. A leftist newspaper outed Röhm as gay. His sexuality was then used in the election propaganda of the moderate-left Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands). Despite the controversy, Hitler defended Röhm. Röhm remained in charge of the SA until Hitler had him murdered in 1934. However, Röhm’s position in the Nazi leadership did not temper the movement’s condemnation of homosexuality and gay communities.

Gay Men in the First Years of the Nazi Regime, 1933–1934

The Nazis came to power on January 30, 1933. Shortly thereafter, they sought to dismantle the visible gay cultures and networks that had developed during the Weimar Republic. One of the Nazis’ first actions against gay communities was to close gay bars and other meeting spots. For example, in late February/early March 1933, in response to a Nazi order, the Berlin police closed numerous bars. Among them was the Eldorado, which had become a prominent symbol of Berlin’s gay culture. Similar closings of gay meeting places occurred across Germany. However, in cities like Berlin and Hamburg, some established gay bars were able to remain open until the mid-1930s. Underground gay meeting places remained open even later. Nonetheless, the Nazi closures and increased police surveillance made it far more difficult for gay men to connect with each other.

Another early action undertaken by the Nazi regime was the elimination of gay newspapers, journals, and publishing houses. Newspapers had been one of the primary means of communication in Germany’s gay communities. The Nazi regime also forced gay associations to dissolve. In May 1933, the Nazis vandalized Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Sciences and ultimately forced it to close. Part of this action included destroying Hirschfeld’s writings in Nazi book burnings. These book burnings targeted works written by prominent Jewish intellectuals, pacifists, and left-wing authors. The destruction of the institute was a clear sign that the Nazis would not tolerate the reformist sexual policies that the institute promoted.

In a further escalation, the Nazis used new laws and police practices to arrest and detain without trial a limited number of gay men beginning in late 1933 and early 1934. This was part of a larger Nazi effort to reduce criminality. The Nazi regime instructed the police to arrest people with previous convictions for sexual crimes such as public exhibitionism, sexual relations with a minor, and incest. These crimes were defined in Paragraphs 173-183 of the German criminal code. Those arrested included a number of gay men, some of whom were imprisoned in the regime’s early concentration camps.

In fall 1934, the Berlin Gestapo (political police) instructed local police forces to send them lists of all men believed to have been engaged in same-sex behavior. Police in various parts of Germany had been keeping such lists for many years. However, centralizing this list in the hands of the Berlin Gestapo was new. In addition, the Gestapo specified that local offices should be sure to note if these men were members of Nazi organizations and if they had any prior criminal convictions under Paragraph 175. These lists have come to be known as “pink lists,” although this was not what the Nazis or the police called them.

These early measures were just the beginning of the Nazi campaign against homosexuality. Nazi actions would escalate in the second half of the 1930s.

Escalating the Persecution of Gay Men, 1934–1936

Three events in the years 1934–1936 radicalized the Nazi regime’s campaign against homosexuality and led to more systematic oppression of gay men.

First was the murder of Ernst Röhm and other SA leaders in June–July 1934. These killings changed how Nazi propaganda talked about homosexuality. Röhm and the other SA leaders were murdered on Hitler’s orders as part of a power struggle at the highest levels of the German government and Nazi Party. But after the purge, Nazi propaganda used Röhm’s sexuality to help justify the killings. In doing so, they played on much of the German population’s prejudice against same-sex sexuality.

Second, in June 1935 the Nazis revised Paragraph 175, the statute of the German criminal code that banned sexual relations between men. Under the new Nazi version of the statute, a wide range of intimate and sexual behaviors could be, and were, punished as criminal. In addition, the Nazi revision stipulated that non-consensual and coercive acts between men could result in a sentence of up to ten years of hard labor in prison. The revision provided the Nazi regime with the legal tools necessary to prosecute and persecute men engaged in same-sex behavior in much larger numbers than before.

Finally, in 1936 SS leader and Chief of the German Police Heinrich Himmler established the Reich Central Office for the Combating of Homosexuality and Abortion (Reichszentrale zur Bekämpfung der Homosexualität und der Abtreibung). This office was part of the Kripo (criminal police) and worked closely with the Gestapo (political police). The notoriously homophobic Himmler saw both homosexuality and abortion as threats to the German birth rate and thus to the fate of the German people.

By the end of 1936, conditions were in place for the Nazi regime to intensify its campaign against homosexuality.

The Peak of the Nazi Campaign Against Homosexuality

The Nazi campaign against homosexuality intensified in 1935–1936. From this point forward, the regime focused less on shutting down gay meeting places. Instead, the Nazis prioritized the arrest of individual men under Paragraph 175. In the Nazis’ understanding, these men were “homosexual” (“homosexuell”) offenders and thus criminals and enemies of the state. Himmler believed that targeting these men was necessary for the protection, strengthening, and proliferation of the German people. He directed the Kripo and Gestapo to diligently carry out a campaign against homosexuality. These police forces used raids, denunciations, and harsh interrogation and torture methods to track down and arrest men whom they believed violated Paragraph 175.

Raids

In the mid- to late 1930s, the police raided bars and other meeting places that they believed to be popular with gay men. The police set up cordons around bars or other locations, and questioned anyone who seemed suspicious. Some men caught up in raids would be released if there was no proof against them. Those whom the police deemed guilty would be tried for violations of Paragraph 175 or, in some cases, sent directly to a concentration camp.

Police raids were public and high-profile displays in the Nazi campaign against homosexuality. Through raids, the police threatened and intimidated gay communities and individuals. However, raids were not particularly effective. They were not the primary means through which the police tracked down men for alleged violations of Paragraph 175.

Denunciations

The Kripo and the Gestapo relied on tips or denunciations from the public to gather information about men’s intimate lives and uncover potential violations of Paragraph 175. A neighbor, acquaintance, colleague, friend, or family member could inform the police of their suspicions. The language people used in denunciations makes it clear that these Germans tended to agree with Nazi attitudes towards homosexuality. Denouncers referred to those they denounced as “effeminate,” “unmanly,” and “perverse.” Unlike raids, denunciations were a very effective tool of repression. These acts resulted in perhaps tens of thousands of arrests and convictions.

Interrogations

The Gestapo and Kripo interrogated men caught up in raids, as well as those denounced. During these often physically and psychologically brutal interrogations, the police frequently insisted on full confessions. Under the pressure of harsh interrogation and torture methods, men were forced to name their sexual partners. This in turn helped the police identify other men to arrest and interrogate. In this way, the police caught entire networks of gay men.

The Fate of Those Arrested

Not all men arrested under Paragraph 175 shared the same fate. Typically, an arrest would lead to a trial before a court. The court would either acquit or convict the accused and sentence them to a fixed prison sentence. The conviction rate was approximately 50 percent. Most convicted men were released after serving their prison sentence. In rarer cases, the Kripo or the Gestapo would send a man directly to a concentration camp as a “homosexual” (“homosexuell”) offender. Typically, but not always, men sent to concentration camps in this way had multiple convictions or other aggravating circumstances.

The Nazi German judicial system also introduced castration into legal practice. As of late 1933, courts could order mandatory castration for certain sexual offenders. However, at least initially, men arrested under Paragraph 175 could not be castrated without their supposed consent. In some cases, men imprisoned under this statute could secure early release if they volunteered to be castrated.

During World War II, the number of men arrested under Paragraph 175 declined. The needs of a total war took precedence over the Nazi campaign against homosexuality. Many men who had Paragraph 175 convictions either joined or were conscripted into the German military. The military needed the manpower and in most cases they considered a soldier’s sexuality to be of secondary importance. Nevertheless, arrests and convictions under Paragraph 175 continued throughout the war years.

Scholars estimate that there were approximately 100,000 arrests under Paragraph 175 during the Nazi regime. Over half of these arrests (approximately 53,400) resulted in convictions.

Gay Men in Concentration Camps

Between 5,000 and 15,000 men were imprisoned in concentration camps as “homosexual” (“homosexuell”) offenders. This group of prisoners was typically required to wear a pink triangle on their camp uniforms as part of the prisoner classification system. Many, but not all, of these pink triangle prisoners identified as gay.

The pink triangle called attention to this prisoner population as a distinct group within the concentration camp system. According to many survivor accounts, pink triangle prisoners were among the most abused groups in the camps. Sometimes pink triangle prisoners were assigned the most grueling and demanding jobs in the camp labor system. They were often subjected to physical and sexual abuse by camp guards and fellow inmates. In some cases, they were beaten and publicly humiliated. In Buchenwald concentration camp, some pink triangle prisoners were subject to inhumane medical experiments. Beginning in November 1942, concentration camp commandants officially had the power to order the forced castration of pink triangle prisoners.

Fearing guilt-by-association, already prejudiced fellow prisoners shunned pink triangle prisoners. Pink triangle prisoners were left isolated and powerless within the prisoner hierarchy. Prisoner networks provided tools of survival, such as access to food and clothing, for many camp inmates. The fact that most pink triangle prisoners were German-speakers provided some measure of protection by giving them access to less onerous work details such as administrative positions. Nonetheless, the typically isolated position of these prisoners made their survival much more difficult. An unknown number of pink triangle prisoners died in the concentration camps.

Gay men could be imprisoned and persecuted in concentration camps for reasons other than their sexuality. Some gay men were sent to camps as political opponents, Jews, or as members of other prisoner categories. In these cases, their sexuality was generally secondary to the reason for their imprisonment. They wore the badge that corresponded to their official prisoner category.

An unknown number of gay Jewish men were murdered in the Holocaust.

Gay Men’s Responses to Nazi Persecution

Gay men responded to Nazi persecution in different ways. Not all gay men made the same decisions. Nor did they all have the same choices. For example, gay men categorized by the Nazi regime as Aryan had far more options than those categorized as Jews or Roma (Gypsies). Jewish and Romani gay men—above all—faced persecution for racial reasons.

Some gay men, especially those with financial resources, could try to hide their sexuality and outwardly conform. Some broke off contacts with their circles of friends or withdrew from the public sphere. Others moved to new cities, the countryside, or even to other countries. Some gay men also entered marriages of convenience.

There were gay men who took the risk of resisting the Nazi state for political and personal reasons. Some gay men joined underground anti-Nazi resistance groups or helped hide Jews.

Documenting and Memorializing Gay Experiences

In spring 1945, Allied soldiers liberated concentration camps and freed prisoners, including those wearing the pink triangle. But the end of the war and the defeat of the Nazi regime did not necessarily bring a sense of liberation for gay men. They remained marginalized in German society. Most notably, sexual relations between men remained illegal in Germany throughout much of the twentieth century.1 This meant that many men serving sentences for allegedly violating Paragraph 175 remained in prison after the war. Tens of thousands more were convicted in the postwar era.

Uncovering the histories of gay men during the Nazi era was difficult for much of the twentieth century because of continued prejudice against same-sex sexuality and the ongoing enforcement of Paragraph 175. Many gay men were afraid to share their testimonies or write memoirs. Nonetheless, scholars have sought to document gay men’s experiences, using police, court, and concentration camp records.

The efforts of scholars and German gay rights organizations have helped to bring the persecution of gay men under the Nazis into the public eye. In the 1990s, the German government acknowledged “persecuted homosexuals” (“verfolgten Homosexuellen”) as victims of the Nazi regime. In 2002, the government overturned Nazi-era convictions for Paragraph 175. For the first time, gay men who had suffered at the hands of the Nazis became eligible for monetary compensation from the German government for injustices perpetrated against them.

In the early twenty-first century, the German government opened four memorials to Nazi victims in central Berlin. The largest is the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, which opened in 2005. A few years later, in May 2008, the Memorial to Homosexuals Persecuted under Nazism (Denkmal für die im Nationalsozialismus verfolgten Homosexuellen) was unveiled nearby in Tiergarten park in central Berlin.

Scholars continue to research the Nazi campaign against homosexuality and the regime’s persecution of gay men.

Series: Gay Men and Lesbians under the Nazi Regime

Critical Thinking Questions

- <p>Compare and contrast the Nazi regime’s policies towards gay men with German policies before 1933 and after 1945.</p>

- <p>How did the Nazi persecution of gay men fit into the broader Nazi worldview?</p>

- <p>What role did denunciations play in the Nazi campaign against homosexuality? What do these denunciations reveal about the relationship between the Nazi regime and the German people?</p>

- <p>How did the Nazis’ treatment of gay men differ from their treatment of other groups? How was it similar?</p>

Germany became two countries in 1949: the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) and the German Democratic Republic (East Germany). East and West Germany took different approaches to criminalizing sexual relations between men. Most notably, West Germany continued to use the 1935 Nazi version of Paragraph 175. Paragraph 175 was dropped from the German criminal code in 1994 after East and West Germany reunited as the Federal Republic of Germany.