The Boycott of Jewish Businesses

Nazi leaders organized a boycott on businesses owned by Jews in 1933. The boycott was the first nationwide anti-Jewish action in Nazi Germany.

The Boycott of Jewish Businesses

The "Jewish boycott" ("Judenboykott") was the first coordinated action undertaken by the Nazi regime against Germany’s Jews. It took place on Saturday, April 1, 1933.

That day, Germans were not supposed to shop at stores and businesses that the Nazis identified as Jewish. They were also not supposed to visit the offices of Jewish doctors and lawyers.

Why did the Nazis call for the boycott?

According to Nazi spokesmen, the boycott was an act of revenge against two groups:

- German Jews

- foreigners who criticized the Nazi regime, including US and British journalists.

This, however, was probably not the main reason. There were other motivations based on Nazi antisemitic beliefs.

First, the Nazis believed and spread conspiracy theories that claimed Jews had too much influence on the economy. Second, they unfairly blamed Jews for the economic devastation caused by the Great Depression. Finally, the Nazis’ eventual goal was to remove what they saw as Jewish influence from the German economy. The boycott was supposed to be a first step towards achieving this.

How was the boycott carried out?

The April 1 boycott took place throughout Nazi Germany, in big cities and small towns. It was scheduled to begin at 10 am and last until 8 pm.

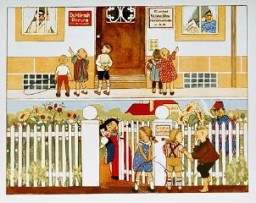

In preparation for the boycott, the Nazis had created lists of businesses that they considered to be Jewish. They stationed uniformed Nazis (called Stormtroopers or SA men) and Hitler Youth members outside of these shops. The uniformed young men intimidated and threatened potential shoppers.

Antisemitic boycott propaganda appeared in business and shopping districts throughout Germany. It took various forms:

- Nazis painted graffiti on store display windows. This graffiti included the Star of David and the word "Jude" (German for "Jew").

- Boycotters carried and hung signs all over cities and towns. A common slogan on such signs was "Germans! Defend yourselves! Don’t buy from Jews!"

- Some non-Jewish business owners posted signs identifying their businesses as "German-Christian," meaning not Jewish.

- Nazis drove and marched through the streets chanting anti-Jewish slogans and singing Nazi songs.

Officially, the boycott was not supposed to be violent. This did not stop some Nazis from beating up and, in a few cases, even killing Jews.

How did Germany’s Jews react to the boycott?

For Germany’s Jews, the boycott was a devastating and noteworthy moment in the early months of the Nazi regime. It angered many Jews, but also frightened others. This was the first time that the new Nazi government officially and publically targeted Germany’s Jewish population as a group and systematically treated Jews as different from other Germans.

Jewish store owners reacted in various ways to the boycott. Many chose to close their shops for the day. They wanted to avoid violence and destruction of their property. Other Jewish store owners defiantly kept their shops open. In a few cases, Jews confronted the Nazi boycotters.

How did non-Jewish Germans react to the boycott?

Non-Jewish Germans also reacted in a variety of ways to the boycott. Some participated in the vandalism and harassment. Some enjoyed the spectacle, but did not directly join in. Others ignored the boycott and went on with their daily lives. Some chose to stay home, because they were scared of confrontation and even violence.

A notable number of Germans deliberately shopped at Jewish-owned businesses. They did so to support their Jewish neighbors, express their opposition to the regime, or show their dislike for the public disorder.

What happened to Jewish-owned businesses after the boycott?

The April 1, 1933, boycott was not the Nazi regime’s last attack on Jewish-owned businesses. But, it was the last nationwide boycott.

Instead, the Nazi regime found other ways to put pressure on Jewish business owners. Local and municipal governments staged their own boycotts. Uniformed Nazis continued to harass Jewish business owners. At the national level, an increasing number of laws and regulations targeted Jewish-owned shops. The vast majority of these stores were forced out of business in the 1930s causing many Jewish families to lose their livelihoods. By the end of 1938, the Nazi regime had almost completely destroyed Jewish economic life in Germany.

Key Dates

1933–1938

Ruining Jewish businesses

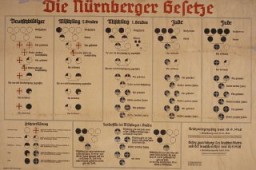

From 1933–1938, the Nazi regime unofficially pressures Jewish business owners to close or sell their businesses. The Nazis use propaganda and threats to encourage Germans to shop at stores owned by non-Jews. Jews are increasingly isolated from the rest of German society. Jewish-owned shops lose previously loyal customers. Longstanding business relationships collapse. Some Jews sell their businesses for a greatly reduced value. Other businesses simply fail. Many non-Jewish businesses and individuals benefit from this process.

November 9–10, 1938

Vandalism during the Night of Broken Glass

On the night of November 9–10, 1938, the Nazi regime coordinates a wave of antisemitic violence in Nazi Germany. Organized groups of Nazis wreak havoc on Jewish life. They vandalize thousands of Jewish-owned businesses, breaking the glass in storefronts. This becomes known as Kristallnacht or the "Night of Broken Glass." It is named for the shattered glass from store windows that litter the streets after the violence. This is a direct attack on remaining Jewish-owned businesses.

November 12, 1938

Decree on the Elimination of the Jews from German Economic Life

In the aftermath of the Night of Broken Glass (Kristallnacht), the Nazi regime increases its efforts to destroy Jewish-owned business. They do so using laws and regulations. On November 12, the regime issues a decree excluding Jews from economic life. Among other things, Jews are forbidden to operate retail stores or carry on a trade. The law also forbids Jews from selling goods or providing services at any kind of establishment.

The decree requires any remaining Jewish-owned businesses to either close or undergo "Aryanization." In cases of "Aryanization," Jewish business owners are forced to sell or even hand over their businesses to non-Jewish Germans.