|

|

African American Athletes

|

|

|

Eighteen Black athletes represented the United States in the 1936 Olympics. African-Americans dominated the popular track and field events. Many American journalists hailed the victories of Jesse Owens and other Blacks as a blow to the Nazi myth of Aryan supremacy.

Goebbels's press censorship prevented German reporters from expressing their prejudices freely, but one leading Nazi newspaper demeaned the Black athletes by referring to them as "auxiliaries." The continuing social and economic discrimination the Black medalists faced upon returning home underscored the irony of their victory in racist Germany.

|

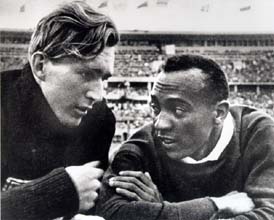

The American press reported widely on the friendship that developed between Owens and his German competitor in the long jump, Carl Ludwig (“Luz”) Long. Long was killed in action during World War II. —USHMM #69562/Courtesy of Dr. George Eisen

|

|

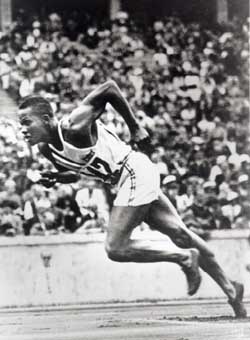

The son of Alabama sharecroppers, Owens was besieged by autograph seekers throughout his stay in Germany. He was cheered loudly every time he entered the stadium by the mostly German audience. July 31, 1936. —USHMM #21726/UPI/Bettmann/CORBIS

|

|

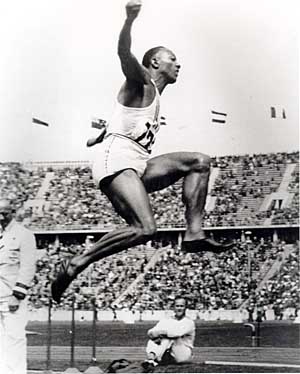

Jesse Owens, “the fastest human being,” captured four gold medals and became the hero of the Olympics. In the long jump he leaped 26 feet 5-1/2 inches, an Olympic record. Immediately after the Games, Owens hoped to capitalize on his fame and quit the AAU's European tour of post-Olympic meets; for this action, the AAU suspended him from amateur competition. August 4, 1936. —USHMM #14519/Bundesarchiv Koblenz, Germany (inventory number 146-1995-066-31A)

|

|

John Woodruff won the 800-meter run, finishing in 1:52.9 minutes. Woodruff served as an officer in a racially segregated American Army unit during World War II. —USHMM #14498/FPG International, New York

|

|

The United States high jump team swept their event at the Olympics. From left to right: Delos Thurber (bronze), Cornelius Johnson (gold), and David Albritton (silver). Johnson cleared the bar at 6 feet, 8 inches, an Olympic record. August 2, 1936. —USHMM #21699/UPI/Bettmann/CORBIS

|

|

“Mack” Robinson took the silver in the 200-meter dash. His younger brother, Jackie, would become the first African-American player in major league baseball in 1947. —USHMM #21719/Courtesy of Mack and Delano Robinson

|

|

Archie Williams, from the University of California, Berkeley, won the 400-meter race with a mark of 46.5 seconds. During World War II, he served as an instructor for African-American fighter pilots at the segregated army airfield in Tuskegee, Alabama —USHMM #14503/Bundesarchiv Koblenz, Germany (inventory number 146-1995-066-19A)

|

|

John Woodruff speaking about his experiences

Loading ...

Transcript:

I was born in a small town about 50 miles south of Pittsburgh, just a small town, right in the mountains. My father was a laborer. My mother birthed 12 children. No member of my family ever finished high school. Only way that I could go to college was through athletics. My parents didn't have the money to send me to school. In fact, I didn't even have... when I received a scholarship to the University of Pittsburgh, I didn't even have transportation to get to school.

In fact I never even thought in terms of going into the Olympics. Never thought in terms of that at all. And it was the coach that approached me on it and said he wanted me to try out for the team. There was one instance when we had a young German athlete come visit with us. And we were asking this young athlete, he spoke English fluently, and we asked him now, what did the people, the German people, think of Hitler? He said that they thought he was a very good man because of what he'd done for the country economically speaking. They thought that he was great for the country. But they didn't realize that they had a Frankenstein on their hands, you see.

There was some talk about the Olympics being boycotted because of what Hitler was doing to the Jewish people in Germany. But it was never discussed amongst team members. We heard something about it, but we never discussed it. We weren't interested in the politics you see, at all, we were only interested in going to Germany and winning.

It was the first time I'd ever taken a boat anywhere. Most of the blacks came from poor families, you see. None of us came from any wealthy homes, or middle class homes, most all from poor families. Jesse [Owens] came from a poor family too. I was very nervous for a young man, 21 years old, I'd never been so far away from home.

My only objective was any time I got into a race was to win. And that's what I did. Determination. That's what it takes. Light a fire in the stomach. I was winning for me and I was winning for the country. Me first, then the country. It was very definitely a special feeling in winning the gold medal and being a black man. We destroyed his [Hitler's] master race theory, whenever we start winning those gold medals. So I was very proud of that achievement and I was very happy, for myself as an individual, for my race, and for my country.

After the Olympics, we had a track meet to run at Annapolis, at the Naval Academy. Now here I am, an Olympic champion, and they told the coach that I couldn't run. I couldn't come. So I had to stay home, because of discrimination. That let me know just what the situation was. Things hadn't changed. Things hadn't changed.

Transcript:

I was born in a small town about 50 miles south of Pittsburgh, just a small town, right in the mountains. My father was a laborer. My mother birthed 12 children. No member of my family ever finished high school. Only way that I could go to college was through athletics. My parents didn't have the money to send me to school. In fact, I didn't even have... when I received a scholarship to the University of Pittsburgh, I didn't even have transportation to get to school.

In fact I never even thought in terms of going into the Olympics. Never thought in terms of that at all. And it was the coach that approached me on it and said he wanted me to try out for the team. There was one instance when we had a young German athlete come visit with us. And we were asking this young athlete, he spoke English fluently, and we asked him now, what did the people, the German people, think of Hitler? He said that they thought he was a very good man because of what he'd done for the country economically speaking. They thought that he was great for the country. But they didn't realize that they had a Frankenstein on their hands, you see.

There was some talk about the Olympics being boycotted because of what Hitler was doing to the Jewish people in Germany. But it was never discussed amongst team members. We heard something about it, but we never discussed it. We weren't interested in the politics you see, at all, we were only interested in going to Germany and winning.

It was the first time I'd ever taken a boat anywhere. Most of the blacks came from poor families, you see. None of us came from any wealthy homes, or middle class homes, most all from poor families. Jesse [Owens] came from a poor family too. I was very nervous for a young man, 21 years old, I'd never been so far away from home.

My only objective was any time I got into a race was to win. And that's what I did. Determination. That's what it takes. Light a fire in the stomach. I was winning for me and I was winning for the country. Me first, then the country. It was very definitely a special feeling in winning the gold medal and being a black man. We destroyed his [Hitler's] master race theory, whenever we start winning those gold medals. So I was very proud of that achievement and I was very happy, for myself as an individual, for my race, and for my country.

After the Olympics, we had a track meet to run at Annapolis, at the Naval Academy. Now here I am, an Olympic champion, and they told the coach that I couldn't run. I couldn't come. So I had to stay home, because of discrimination. That let me know just what the situation was. Things hadn't changed. Things hadn't changed.

|

|

The Museum’s exhibitions are supported by the Lester Robbins and Sheila Johnson Robbins Traveling and Special Exhibitions Fund, established in 1990.

|